Welcome to The Bad Beekeeper's Blog

2008 Blog 2009 Blog 2010 Blog 2011 Blog 2012 2013 Blog 2014 Blog 2015 Blog

Another year over; and what have we done? Here's the state of beekeeping at the end of 2012...

|

It seems that the strange syndrome beekeepers call "Colony Collapse Disorder" was not so bad this year. CCD has been blamed for poor wintering in recent years - in Canada, losses had averaged over 20% for the past decade. Manitoba was particularly hard hit, with 30% of colonies dead for each of the past 5 years (up to 2011). Without replacements, 1000 hives would become 700 the first spring, those would dwindle to 490 the next spring... down to about 170 colonies in the spring of the 5th year. This is frightening stuff. To keep at a constant 1000 per year, the average beekeeper in Manitoba - one of Canada's best honey provinces - would have split, bought, or stolen 300 hives a year. That's 1500 colonies in the five years. An awful lot of replacements. But in the spring of 2012, those beekeepers found a more sustainable 16% loss. Finally, a normal number!

Here in Alberta, CCD was also less apparent - wintering went well and the honey crop improved over recent years. Alberta beekeepers produced 20% more than last year - making 40.5 million pounds of honey 144 pounds (65 kg - or a smidgen o'er 10 stone, if you're a Brit) per hive. Overall in Canada, the number of managed hives has jumped up 10% to something over 700,000 colonies. This ties the record colony count from back in the mid 1980s - and is up a lot from just a few years ago (in 2006, Stats Canada counted just 554,000). So if colonies are "disappearing" it's not here in Canada - at least not during 2012.

The past year saw Bayer (your headache company) in the news quite a bit. A very serious study conducted by the Harvard School of Public Health linked Bayer's pesticide imidacloprid to Colony Collapse Disorder and published the findings in June's Bulletin of Insectology. (You can get a copy of the complete paper here.) Imidacloprid is a systemic neurotoxin insecticide,

available everywhere fine insecticides are sold - check out this link on Amazon.com. ($40 will make 100 gallons of the toxin, if you like.) The stuff is considered relatively safe around humans,

according to the US government's EPA, but it does a number on "sucking, chewing, biting insects" - fleas, termites, roaches, aphid, and perhaps your bees. The Harvard study thinks so, but Bayer begs to disagree. Bayer has fought back, saying the Harvard study is "factually inaccurate and is seriously flawed, both in its methodology and conclusions." Bayer added that "All new bee research involving bee health is welcome and great care should be taken to avoid sweeping, unsupportable conclusions based on artificial and unrealistic study parameters that are wildly inconsistent with actual field conditions and insecticide use." Indeed. And, as if to prove its love for all things honey bee, the German pharma-chemical enterprise (which is worth $70 billion and posted a $3 billion profit last year) established a 3 million dollar bee research station in Durham, North Carolina, associated with the university there. They will keep about 40 colonies of bees for research and apparently focus on the small hive beetle and varroa mite. Bayer's project manager, Robyn Keene, says that Bayer is dedicated to sustainable agriculture.

available everywhere fine insecticides are sold - check out this link on Amazon.com. ($40 will make 100 gallons of the toxin, if you like.) The stuff is considered relatively safe around humans,

according to the US government's EPA, but it does a number on "sucking, chewing, biting insects" - fleas, termites, roaches, aphid, and perhaps your bees. The Harvard study thinks so, but Bayer begs to disagree. Bayer has fought back, saying the Harvard study is "factually inaccurate and is seriously flawed, both in its methodology and conclusions." Bayer added that "All new bee research involving bee health is welcome and great care should be taken to avoid sweeping, unsupportable conclusions based on artificial and unrealistic study parameters that are wildly inconsistent with actual field conditions and insecticide use." Indeed. And, as if to prove its love for all things honey bee, the German pharma-chemical enterprise (which is worth $70 billion and posted a $3 billion profit last year) established a 3 million dollar bee research station in Durham, North Carolina, associated with the university there. They will keep about 40 colonies of bees for research and apparently focus on the small hive beetle and varroa mite. Bayer's project manager, Robyn Keene, says that Bayer is dedicated to sustainable agriculture.

|

|

2012 was not all about colony collapses and neonicotinoidal imidacloprid pesticides. There was some lighter news. In December, we learned that honey bees were being trained to stick their tongues out. Some top-notch scientists at Bielefeld University in Germany are teaching bees as smart as Einstein to stick out their tongues whenever their antennae encounter a particular type of material. Very Pavlovian-dog style here:

The bees are rewarded a drop of sugar syrup (for which they naturally extend their tongue) whenever the feel of the test material is right. The smart little bugs soon start sticking their tongues out before getting fed, in anticipation of their treat. Behavioral biologist researcher Dr Dürr says, "If you can train an insect to respond to a certain stimulus, then you can ask the bees questions in the form of 'Is A like B? If so, stick your tongue out." Maybe Dürr can link up with Bayer and see if test results are improved with the help of the nerve toxin neonicotinoids, or not?

In France, bees started producing some colourful honey - blue and green, actually. Seems they gained unauthorized access to a biofuel 'plant' which was firmly rooted in the green concept of converting left-over candy pigments from a nearby Mars factory's M&Ms shells into energy. Who could resist? The biofuel plant has tried to stop the neighbourhood bees from pilfering the yummy M&M ingredients by keeping trash containers covered and windows shut.

Although the stuff tastes like honey, the unfortunate beekeepers aren't allowed to sell it. Their honey is tainted by artificial dyes and processed sugars the bees sneaked home. Sure, it is perfectly acceptable to feed the same stuff to children as candy, but they make the beekeeper dump the M&M honey. I guess it protects the brand, but it is still sad for those beekeepers.

Bad news: a deadly fly parasite was spotted for the first time on honey bees, reported researchers at San Francisco State University in 2012. The fly, Apocephalus borealis, deposits its eggs into a bee's abdomen. After the honey bee dies, fly larvae "push their way into the world from between the bee's head and thorax". (I hope you're not eating breakfast right now.) After the parasitic fly has laid those eggs, the bees abandon their hives in "a flight of the living dead" and hang out near lights. See if you are following this: bad fly lays eggs in honey bee's bottom, which hatch into worms, which creep out from inside the bee, which is driven mad and flies off with the parasites at night to hang out under street lamps. These zombie bees frequently carry the deformed wing virus and Nosema ceranae fungus, according to John Hafernik, Andrew Core, and Geraldine Lindsay, who have been studying this phenomenon. There are a number of unanswered questions about the parasites and the affected bees, so the researchers say they will radio tag the bees and video monitor them in their next round of study.

|

Good news: the indigenous black Irish honey bee is making a come-back. The native honey bee was deemed extinct in some parts of Ireland, but in 2012, researchers found it in various pockets throughout the British Isles - Londonderry, Isle of Man, Lancashire, even West Sussex where some say almost nothing survives. The black bees (Apis mellifera mellifera) are claimed to be better suited to the UK's cool wet dark climate than the more common commercial bee, the Italian (Apis mellifera linguistica) which evolved in the warm dry sunny climate south of the Alps and north of Sicily.

I have had a couple of great opportunities to see these famous black bees. When I was a kid, I helped a farmer named Senator Bill Graham in South Carolina sort through his bees. In a shady pine grove, he had a few hives that hadn't been touched in years, he said. I was amazed at how dark the bees were. And runny. They flowed like water around the frame, off it, over my hands, down into the deep super below. It was impossible to find the queen among these flighty insects. These were descendants of America's original European bees and they were already rare. I knew of only those few hives down along the Great Pee Dee River.

My other opportunity to see black mellifera mellifera bees came many years later, in 2005, when Ireland hosted Apimondia. My daughter Erika and I signed up for the Galtee Queen Breeding Group's station tour. The bees were as black as advertised. But much calmer than the ones I'd seen in the southern USA. These bees stayed on the combs. To your right is a photo I took of one of the Galtee mating nucs.

|

From the UK this year, scientists published in Biology Letters that bees frequently mess up their waggle-tail dance if they are describing nectar sources that require the bees to dance horizontally across the frame. Much better for them to dance straight up or down. Going horizontally, gravity tugs the dancers off course, thus throwing the listening foragers off course. This research discovery is the result of patiently watching 198 individual waggle dances and comparing the dances with the flight angle that bees were (apparently) trying to signal. The scientists' data also suggests that if the dancing bee can't repeat the dance with the same angle, other bees in the hive laugh at her incompetence and then ignore the directions. The message here for beekeepers might mean that we need to line up our hives so the hive, mid-day sun, and field of forage are on the same straight line. That would lead to an up-down dance and less confusion. Or, as a beekeeper, you might just want to find a spot surrounded in nectar sources in all directions so the bees can quit gabbing and just collect.

Finally, in this mini-summary of last year's bee news, we learn that bees are just like you and I when it comes to thrill seeking adventure. In fact, the New York Times reported the news as "Brains of Bee Scouts Are Wired for Adventure". I thought so. Dr Gene Robinson, a geneticist at the University of Illinois, wrote in the Journal Science that there are "massive differences in brain gene expressions between scouts and nonscouts." The scientists found that by increasing certain chemicals in the bee's brain, a timid bee would become a thrill-seeker. Time magazine reported the same story in a different manner: Bees Have Distinct Personalities, reporting that "some bees are thrill-seekers always looking for a new experience" - which can be satisfied by enlisting in the bee scouts.

|

This year's blog didn't describe my own beekeeping at all. I wrote a little about other beekeepers. And I wrote a lot on thoughts and ideas I've had with bees in mind. But not much on the wholesome good fun of getting sticky with propolis, or feeling the warm glow that a hundred stings on the finger tips can give you. I didn't write much about poking around in the bees because 2012 was the first year since 1970 that I didn't manage a beekeeping outfit.

I was 16 in 1970, freshly and dangerously armed with a driver's license, given the keys to my family's 300 hives of bees. I didn't do well, but not badly, either. The weather was good and I ended that season with a hundred 60 pound tin cans of buckwheat honey and a couple drums from black locust.

|

Saskatchewan or Bust. I arrived in western Canada with an ancient truck, some rudimentary beekeeping skills, and a lot of enthusiasm, becoming a Canadian beekeeper at age 22. Saskatchewan had great conditions for beekeeping. Setting up in a cattle town called Val Marie, I ran a thousand hives and had a few good years - one summer getting over 300 pounds of honey per hive. It was remarkable. I was still clumsy and inept, had a lot to learn, but some of the hives each gave me 700 pounds of white thick clover honey. It was remarkable. After three or four years of walking on clouds, my luck ran out with the honey gods. A devastating drought destroyed the ranchers around me; my hives suddenly made nothing. Good Beekeeping to Bad Beekeeping in just a few months. I sold most of my bees - kept just a couple hundred hives - and headed for university in Saskatoon. Four years later, I emerged from the greystone campus as a geophysicist, moved farther west, and found a place in the Rocky Mountain foothills to park a dozen hives of bees near my new home in Calgary.

For a dozen years, with a dozen hives, I was a hobby beekeeper. Then one of my older brothers decided to move to Canada. We began to build up a new small business. The thing grew to four or five hundred hives - all of them producing beautiful combs of honey - nothing extracted; just comb honey. We very tediously developed a market for comb honey - a great product that lots of consumers had never seen before and couldn't seem to figure out. Surprisingly, they didn't seem to know they needed it. After a few years, my brother and his wife left Canada, mostly so they could live closer to their son back in the USA. The timing was good - the farm and business passed along to my daughter, Erika, and her husband, Justin. Erika is a dynamic marketer and quickly expanded the farm's sales all around the world. She sold the entire crop her first year - she could have sold twice as much honey if the bees could produce it. So her husband - who has a natural talent at beekeeping - will try to double the colony count next year. They are a good team, keen and hard-working. The young people now running Summit Gardens Honey did well enough in 2012. I think the bees will be OK.

|

Are we melting? When I was a kid, I learned that the world was heading back to another ice age. The argument was reasonable enough. Some evidence presented in charts, graphs, and photos showed that the 1970s were the tail-end of a mild period between global glaciers. Our grandchildren would have to deal with icy summer mornings and ever-deepening snow drifts. (However, even back in 1970, many other scientists were already predicting global warming, due to fossil fuel use - but the Ice Agers were still pretty persuasive.) An icy forecast doesn't seems so likely today. And so it is with science. We amass data, make interpretations, publish conclusions. Forecasting is not really science in the strictest sense. Science uses repeatable experiments, it tests hypotheses with control samples. You may be lucky enough to discover something new by controlling variables and observing results. But great discoveries rarely result in a scientist running naked through the streets, shouting, "Eureka!" - instead, the scientist is more likely to mutter something like "Hmm? What's going on here?" when interesting results are noticed.

History is littered with scientists who became minor footnotes by failing to notice the implications of their findings. And it is just as frequently littered with the debris of great thinkers who could not adjust to the implications of new ideas. At the time we were anticipating the next ice age, most aging geoscientists dismissed a silly concept called "continental drift". Although Wagner proposed the idea of floating continents in 1912, his theory was still being dismissed as late as 1968 by the established earth scientists who saw the concept as fringe science. Predictions of a coming Ice Age and rejections of Plate Tectonics were among the prevailing ideas in science, not that long ago.

Global weather science doesn't allow rigorous scientific experimentation. We can't make guesses (hypotheses) and run experiments, while keeping a controlled, non-varying sample world at the other end of the lab table. There is only one Earth. We can't go back and try again, adding less carbon dioxide to see the air to test what would happen. We can try computer modeling, but we are limited by the variables we know are important to the simulations. We aren't likely to get them all added into the mix. Nevertheless, the simulation results so far are portentous. And the observed results - from Katrina and Sandy to disappearing arctic ice to submerging island nations - are scary. I'm not going to claim that we know with definitive certainty that the globe is irreversibly heating up. Probably. But not certainly. Is the releasing of billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere the cause of weather change? Probably.

So what does climate change mean for beekeepers? Here in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, we've had a warm October. September had been one of our hottest on record. October began with a high of 23 (about 72F); bees collected pollen off-and-on through the month, undeterred by a light October frost. (Decades ago, the killing frosts were in September.) The bees went on to enjoy days and days of mild temperatures - unusual for October. For example, on October 15, the overnight low was 10C (50F) which is downright balmy for mid-October in Calgary. But it makes no sense to pick individual days (current or historical) and use them as the basis of any argument. The meaningful statistics are in the long-term averages. In the USA, 2012 joins the years from 2001 through 2011 as the very warmest on record. Of all the weather events in 2012, the most ominous to climate scientists is the loss of ice cover near the North Pole. In September, scientists at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in the USA reported that Arctic sea-ice measured almost 20 per cent less than the previous record low, set in 2007. The mid-September ice cover was about half the average of the 1980s and 90s. This extra billion acres of exposed water absorbs more heat, increasing the water temperature and melting even more ice. The Canadian government weather scientists - when not muzzled by their political bosses - will tell you that the Arctic Sea may be without any ice cover as early as the summer of 2016. Even Exxon's big boss, Rex Tillerson, has recently acknowledged the reality of global climate change - although he is pretty sure we can engineer our way out of its worst consequences. (From The Guardian, "In a speech on Wednesday, Tillerson acknowledged that burning of fossil fuels is warming the planet, but said society will be able to adapt.")

You need to be aware that beekeeping may change dramatically with climate change. In general, climate changes are expected to bring hotter weather for the northern plains and prairies of North America's mid-section. This could be a good thing for beekeepers around here - if droughts like this summer's desert weather don't become the norm. Other North American beekeepers may see more flooding in coastal apiaries and more droughts in southern croplands. How does the beekeeper prepare for this? If ever there was a time to be more efficient and to plan ahead, this is it. A beekeeper can organize bee routes in a way that will reduce environmental impact and save money. The beekeeper also needs to be aware that good crops might be far better than ever, with huge bumper crops requiring a bigger stack of supers and some extra harvesting help; however, poor years might be even worse than awful - requiring feed for bees and extra precautions against drought-enhanced fires. To handle the really bad years, cash from the good years needs to be prudently saved. It will be more of a roller coaster adventure. All farming will be riskier, but beekeeping will probably suffer the greatest variations. In an area where hundred pound crops are the norm, several years without harvests may be followed by a year or two when the honey gods turn on the nectar flow in the spring and forget to shut it off again. But it is a lot more likely that things will go badly wrong - too much rain, or too little; too much sweltering heat, or an untimely frost. There are more things that might go wrong than will be compensated by things going better than usual.

The greatest single variable in honey production is the weather. Weak hives will sometimes make a fair honey crop. But with really bad weather, the best hives make nothing. In Canada's wine country near Niagara Falls, William and Steve Roman report a season two weeks too early and less than half their norm, according to a Globe and Mail piece called, "Gold Rush: Harvesting honey on a wild weather schedule". Meanwhile, PBS, America's non-commercialized network, tells us "Unpredictable Weather Causes Pain for Beekeepers" and explains how Jeremy Jellinek of Michigan lost $100,000 this past season keeping bees. Jellinek told PBS, he "worries that more unpredictable weather patterns may further destabilize his business." For a balanced and more scientific assessment, take a look at "Beekeepers Abuzz Over Climate Change and Hive Losses" in the Scientific American magazine.

|

Our friend Jacques died today. I hadn't seen him in a few months - I had been recovering from back surgery gone seriously wrong and Jacques was in poor very health himself. So our repeated plans to meet up, to smell the grass in front of his urban beehive, just couldn't be arranged. However, last week, Jacques was feeling quite a bit better, so he and his wife decided they could come visit us at our house. They would visit on Sunday afternoon for an hour or two of coffee, cakes, and bee-talk. It didn't happen. A few days before we could commune, Jacques died. Peacefully, at home, at night. A sleep that never ended. In spite of his long and serious illness, he had been making plans to visit the Quebec cottage, to travel a bit, to have a couple more bee hives.

I learned much from this smart, calm gentleman. Jacques was a friend, and his passing was tragic news. Although sick, he sounded upbeat when I spoke with him a few days before his death. He was just in his early 60s - middle-aged by today's reckoning. We connected through the honey bee when Jacques contacted my brother Don a few years ago. Jacques drove out to the farm - an hour from Calgary - and hung out, lent a hand with the bees. He was new to beekeeping and brought the zeal and enthusiasm of a convert. I learn a lot from new beekeepers. They ask the sort of questions that make us old grizzled life-long professionals think about our habits and revise our routines.

With newbies, I'm forced to think through my procedures. I am compelled to reduce my apiculture nomenclature to clear and concise phrases that help me understand what I do better. Have you ever noticed this yourself? Whatever it is you do well and do frequently, teaching it someone new helps you get a better sense for it yourself. I try to spend an hour each year at an elementary school, exciting kids about bees. I try to answer some of my frequent mail from beginners, exciting adults about bees. Having a friend like Jacques was a joy.

Jacques kept a few hives next to his house where he tried to watch them work every day. It was a new passion for him. Jacques had spent his life as a respected teacher and a counselor. He was wise and generous to his friends, to his seven children, and to anyone he encountered. In his early years, he had stowed away on a ship sailing the coast of Africa. A little later, he was watching the streets of Tehran from a roof top when the Shah was deposed. He was an acquaintance of Prime Minister Trudeau's son, and he was a political activist. He was a French-Canadian who had lived most of his life in English-speaking western Canada, but he had a house on a lake near Montreal. He had squeezed a lot of living into his limited years. Jacques found a special passion working with us on the farm, where – through his eyes – he would subtly remind us of the wonder of nature; he encouraged us to look at the world with fresh eyes. We will miss this wonderful man.

|

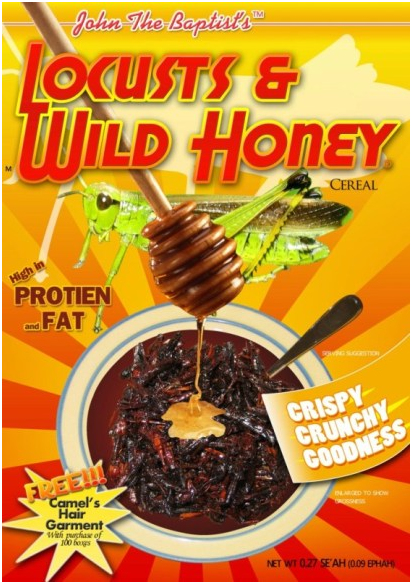

Yummy. The on-line feeder blog, The Daily Meal, has a provocative article this month: Beekeeping Out; Locust-Keeping In. The short article extols the virtues of chewy bugs as alternative food sources for desperate folks in Saharan Africa. It does not explain how raising grasshoppers supplants keeping bees. Instead of mutually exclusive, there could be some synthesis here. In the fall, one might feed old drones to the locusts - ground up and treated with growth hormones and antibiotics, of course.

The Daily Meal's story arises from something America's National Public Radio recently broadcast regarding some enterprising young folks who are developing a "Locust-growing Kit" suitable for distribution to refugees in Africa. The NPR story explains environmentally friendly insects-as-food cuisine, saying, in part: "...grasshoppers, crickets, and beetles are four times more efficient at converting grasses into protein-packed meat than cattle. Insects generate less greenhouse gases than cows, eat just about anything and survive in dry, inhospitable environments." The developers of this food kit are industrious industrial engineering students at L'Ecole de design Nantes Atlantique in France. If people don't immediately eat the kit's produce, they can probably at least introduce the hoppers to colonize new areas, where the bugs might later be harvested in huge amounts using butterfly nets.

But I can not write about locusts in a beekeeping blog without mentioning my favourite Bible character, John the Baptist. The eminently readable New Living Bible version tells us: "John's clothes were woven from coarse camel hair, and he wore a leather belt around his waist. For food he ate locusts and wild honey." Readers of this blog know that I'm a spiritual person, but not religious - which means I'm not much different from about ninety per cent of the people in Canada. But I occasionally read blogs and websites written by apparently religious folks. One cool blog belongs to a British group, Inspire Church, which has a warm welcoming atmosphere on their website and especially in their decidedly unsanctimonious blog, which is worth a look and see. Along with the picture of a box of cereal, right, which they have graciously permitted me to pilfer, I need to give extra credit to the graphic artist who designed it - Mike Costanzo. Inspire Church tells us in an adjacent blog entry: "Jesus message to the fishermen was very simple – no ethical injunctions, no doctrines to sign up to, not even a call for repentance – just “Follow Me”. We try to be as inclusive as this at Inspire Church so whatever you believe – and even if you don't! – why not come along to find out more. 10am. Sunday. Inspire Centre. Everybody’s Welcome Here!" If I were a joiner sort of person rather than an outcast, and if Levenshulme, England, weren't so darn flip-side of the world from Calgary, I would want to meet these folks who are a "...lively bunch, made up of people from all walks of life: young, old, single, married, black, white, gay, straight."

As for John the Baptist. What's not endearing about a hermit who smells like a wet camel and has grasshopper legs stuck to his teeth? But before we cast a too admiring net, we should give some space to the fact that many nay-sayers are suggesting that John's locusts were actually carob beans - which are also known as Saint John's Bread. Carob is a substitute for chocolate (if anyone should wish to make that mistake) and is a high-protein bean found in abundance on tall carob trees in Palestine. These would have fed the prophet, though less romantically than crispy six-legged creatures. (By the way, Leviticus (11:22-32) allows locust-eating. Four varieties of locust are listed in the Torah as kosher.)

I'd like to end this bee blog entry by swinging back to the locusts and wild honey theme. Years ago, in Val Marie, Saskatchewan, I made a great honey-carob candy that sold in a few health-food stores. I bought fifty-pound cases of powdered carob, heated it while mixing in warm honey. (Seeds and/or nuts could be added at this stage.) The mix was poured on to a marble cooling slab where it was spread out into a thin layer. After an hour, we sliced it into bite-sized pieces and boxed it up. That was truly yummy way to enjoy locusts and honey!

|

We had some great fireweed growing beside the deck this month. And we didn't even need to burn any grass to get it. I'm not sure why this lover of scorched earth decided to sprout gratuitously in our undisturbed backyard, but the honey plants shot up two metres (six feet), flowered for a month, and was often covered with bees. Some people would mow it down as a nuisance - a noxious weed - but it is a pretty flower and blooms for weeks. As a honey plant, fireweed is a fickle nectar-producer. It quickly colonizes forest areas that have suffered fires, sprouting up everywhere and sometimes covering dozens of square kilometres. Beekeepers occasionally follow these fires (which they didn't start, honestly) and plant apiaries among the flowers. Sometimes they make a hundred pounds of honey (per hive); more often, they make a hundred pounds of honey (per bee yard). It is quite a chore to chase fireweed for honey. It might do well for a year or two following a forest fire, but then the density decreases as the weed is crowded out by other, less noble, species. Beekeepers in western Canada and Northwest USA have to scout for locations, move the bees perhaps hundreds of kilometres/miles, and usually they need to put up big fences to keep bears out of their lives.

I've seen fireweed honey at specialty honey shops in the west. Never tasted it, but in all the literature, it is described as having a 'distinctive flavour'. Of course, so does broccoli. The typical colour is white' - a technical, legal description of the darkness of honey. Some of the fireweed honey I've seen was 'dark amber' so I'm not sure it was what it was supposed to be. Probably wasn't. Or if it really was, the honey was over-heated during bottling. If you'd like to see a real live hobby bee business making fireweed honey up in Canada's Yukon, here is a video with bees and people in action, though it's not totally clear they are extracting fireweed honey - but that's what their movie's title claims.

By the way, fireweed is sometimes called 'Willow Herb' up here. That's the encyclopedic entry made by John Lovell in his seminal 1926 tome, Honey Plants of North America, He devotes over 2000 words describing the plant's habitat, nectar production, and honey qualities. According to Lovell, willow herb is common throughout northern Europe, Asia, and North America. Lovell's description: "A perennial herb, 2 to 8 feet tall, with long, lance-shaped leaves, and handsome red-purple flowers in long spike-like racemes. After forest and brush fires it springs up in great abundance, and flourishes for about three years, when other plants crowd it out." He continues to outline fireweed's American distribution (Labrador to North Carolina along the Appalachians; abundant in New England, northern Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota; ubiquitous in the northern Saskatchewan and Alberta parklands; but, "it is most abundant in British Columbia both in the mountains and on the coast"); Lovell writes that fireweed has a more northerly range than any other honey plant of first rank. (So, perhaps my idea of keeping bees on Baffin Island near the North Pole as a future retirement project is justified after all!)

Lovell describes fireweed honey as water-white to white, dense, very mild flavoured. John Lovell says production is extremely unpredictable - good colonies sometimes gathering nothing, while in other locales and other seasons, he enumerates colonies gathering 250 pounds (Northern Michigan), 100 pounds (Ottawa), and an outstanding 550 pounds from each of two hives in 1925, in New Westminster, British Columbia. I don't know if the fireweed in my back yard in Calgary has contributed 550 pounds to any neighbour's backlot hive, but it certainly fed a lot of bees from time to time this month. I don't know if you can buy fireweed seeds - probably not. Maybe it's sold as willow herb? You might find it described that way in your favourite noxious weed catalogue when searching for it next spring.

|

Well, the bees are getting a bad rap in Britain. Here's a headline from a Herald Sun newspaper this month that shouts, "BEE stings kill as many people in the UK as terrorist attacks do". We don't doubt the veracity of this story because the article's subtitle headline adds, "a government watchdog report claimed today." Government watchdogs? Dobermans or Rat-Terriers engaged in the bee-sting body count business? I'm not surprised. Actually, the government watchdog is David Anderson, aka the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation. His official report lumps wasps, hornets, and a hundred species of bees into the group responsible for five "bee" sting deaths in 2010 - in all of the United Kingdom (home to 63 million people). Five unfortunate fatalities - some municipalities would ban bees on the basis of this perceived excessive danger. But baths are even more deadly, hence many Brits have banned bathtubs and showers from their homes already, best I can judge from several trips on the London tube* - Bathroom dangers were the source of 29 deaths in 2010.

(* Just kidding about the Brits on the subway! In a recent survey of Europeans,

the Brits place ahead of the French in baths per week.)

British bathtubs are six times more dangerous than bumbling bees and their wasp-ish cousins. Over the past two years, no Brit was killed by a Terrorist. Zero. So, the hundreds of millions spent on watching terrorists may be over-kill, so to speak, according David Anderson, the government-paid watchdog who will probably be losing his job soon. But maybe spending those millions prevented attacks by fundamentalist loonies of all stripes and saved four or five deaths each year. We will never know. It should be noted, says the article, that the Director General of MI-5 (whose funding would be reduced if Britain's conservative government took this report seriously) is pleading quite the contrary to the watchdog report. Claiming instead that "at least 200 known Britons were currently receiving terrorist training at militant camps in the Middle East." Here in Canada, we can be grateful we have a Conservative government (elected by 39% of voters) who came into office on a platform of austerity and reduced spending. They are not likely to squander money on excessive terrorist-watching, mega-prisons, war planes, tributes to foreign royalty, or other nonsense. OK, maybe Canadian Conservatives are as likely to squander our money as conservatives everywhere are...

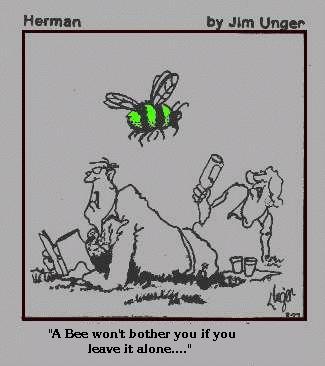

Finally, let me note that the difference between the dangers of bees and the dangers posed by terrorist fundamentalists are palpable. The terrorists are contributing nothing to society, are generally unremorseful (think of the smirking Anders Behring Breivik of Norway), and have the intention of murder. The bee has no evil intent. Unlike the fundamentalist, as everyone knows, a bee won't bother you if you leave it alone.

A friend sent this to me:

"Spring has sprung,

But the bees are not swarming...

Could this be due to global warming?"

I like this little ditty - it works on so many levels. It's May. Here in Calgary, finally, belatedly, 'Spring has sprung" - the leaves are just now opening on the willows and poplars. Pollen has been blowing for only a week or so. A late spring is normal for us at Calgary's high elevation and latitude. It is May and there is still a chill in the air; yet, in a few weeks it will be too hot to polka in the street. I think climate change is like that - too cool, then much too hot. Global warming is certainly a reality. The ice cap that once formed a stylish toque over the globe's bald head is melting - watery-eyed earth is about to get really wet. It has happened before, many times, but this round is on us and our myriad chemicals and exhausts. I guess if we treat our air and oceans as garbage dumps, we deserve what we're going to get. But it's too bad that the other animals on the planet have to suffer for our indulgences and indolences. However, I think the bees will eventually be OK, even if we are not.

In my meagre effort to stay informed about bees, beekeeping, and beekeepers, I occasionally creep around the internet, stalking new ideas, and sometimes marvelling at the bad beekeeping I find in cyberville. Here is an amazing statement from a hobby beekeeper, perhaps a Yuppy type, probably a very nice human, but possibly lacking a connection to practical reality. I saw this statement on the organic beekeepers group, over at Yahoo.

"I picked up my package this past Saturday and it was about an hour away.

My daughter had it on her lap on the front seat.

I have a Mazda RX7 sports car. They calm down.

We even had a loose bee in the car and my daughter

had it on her finger and was talking to it."

|

To which an experienced beekeeper replied, "Right. And it never occurred to you that if you got into a fender bender and the air bag went off, the package would have been crushed and your daughter would have been stung hundreds of times ..."

I include this blog entry not to show contempt for the artsy-fartsy crowd which squanders the Earth's resources on sports cars, but rather I am trying to point out shallow-thinking syndrome. The beekeeper - even the hobby beekeeper - needs to think clearly all the time, or things will go wrong - people may die. It's so easy to make a mistake; so hard to fix one. Whether deciding to requeen, to split hives, to add supers, to harvest early or late, or to allow a young passenger to balance a package of bees on her lap at 120 kilometres an hour, the beekeeper's ability to make smart choices is important. Or maybe not - sometimes bees do stupendously well, regardless of how poorly the beekeeper performs. However, it's the beekeeper who drives the consumptuous sports car, not the bee.

|

On March 30, we usually celebrate World Apitherapy Day at our house by eating fried drone brood seasoned with dandelion pollen and buckwheat honey, while receiving a few intentional bee stings on our finger tips. What a fun day! World Apitherapy Day is celebrated on March 30 because that's my birthday. And, coincidentally, Filip Terc, considered the Father of Modern Apitherapy, shares my birth date. But he was born in 1844, and I was not, so we are not the twins most people think we are. And my sporadically produced blog is more current than his. Terc spent much of his scientific career in Maribor, Slovenia, exploring the benefits of bee-sting therapy on patients of rheumatoid arthritis and other disorders. He was mostly successful with his sting therapies. He published his results in 1888 in a Vienna medical journal. The first modern scientific account of apitherapy.

A lot of people take the apitherapy concept very seriously. Mostly because it can be successful treating ailments that conventional medicine has failed to cure. Normally, we think apitherapy means bee stings. (Or "bee bites", among people who don't know much about bees.) But in addition, apitherapy also includes beehive goodies such as royal jelly, pollen, beeswax, propolis, brood, and (of course) honey. All of which have some real health benefits, albeit perhaps exaggerated benefits.

One of the nice things about apitherapy - it is almost universal. Unlike odd seed pods from the Himalayas or poison from Amazonian red-eyed tree frogs, the honey bee and her medicines can be found nearly everywhere. A person can usually find someone to apply bee stings to swollen joints or propolis tinctures to open sores. And just as discoveries are yet to be made in exotic locales, the full potential of bee products has not yet been uncovered. If you are lucky enough to live in my beautiful home town of Calgary, you could visit our friends, Art and Cherie. They operate a beekeeping business just south of the city which includes many apitherapy products among their honeys and honey wines.

One apitherapy product which is under-rated as a health food is certainly comb honey. Delicious, of course, but healthy, too. Natural, unprocessed, unfiltered - untouched by humans or machines. Eat comb honey. Regularly. It will reward you. With regularity.

Got the mid-winter missin' messin' with them bees blues? Me too. So, here's a link to a great video, Beekeepers of Kenya , that should help you survive this dismal season. The film shows beekeepers using western-style hives, keeping bees in Africa. Watch the whole video, and you will see the harvest being filtered into pails. Beautiful stuff. I suspect - and sincerely hope - that Africa will one day be a prosperous continent. Reform, followed by prosperity, has followed quickly behind the growth of beekeeping in other places, too.

Like most former North Americans and European kid-beekeepers, I grew up believing that most honey is produced in July, after a long cold winter had ended. It did not occur to me that the upside-down people had their seasons reversed and were warming up their humming extractors in February. It's true that much honey is gathered in Canada, Russia, central Europe, the northern USA.

However, honey making has spread far beyond areas mimicking the honey bees' original climate zones. In a remarkable testimonial to the bees' fantastic adaptability, the honey bug prospers in Brazil, Australia, Mexico, Vietnam, India, and Belize. These are not the native homelands of our honey bee, Apis mellifera subspecies - yet today, more honey is produced in the jungles of these hot climates than on the prairies of the north. As an example, Canada makes around 25 thousand tonnes a year (50 million pounds), but Iran 36, Ethiopia 44, and Mexico 56 thousand tonnes of honey. The hottees have it.

Ron, on Acumel Beach in Mexico,

waiting for another nut to fall...To get through our frigid Canadian winter, we usually slip down to Mexico for a few days. This year, we ended up in Acumel, north of the Belize border. When I was young, I knew a gentleman in Florida who owned a couple thousand hives in Central America. The Yucatan Peninsula is honey-heaven for tens of thousands of colonies of Apis mellifera. The neighbouring nominally English-speaking country of Belize (formerly British Honduras) shares the nectar-rich Yucatan with Mexico, so it would not be surprising to learn that an enterprising young American might set up a honey farm there. The thing that surprised me, though, was the beekeeper would routinely leave his Florida ranch and drive down to Central America in his truck to check on his more southerly bees. That's about 3500 kilometres (2300 miles) - the same distance I was hauling my bees from Lake County, Florida, to Saskatchewan, Canada at that time. His trip seemed a lot more exotic to me than mine.... But that was a long time ago - I doubt he's making that trek any more. (And my long-haul own adventure ended thirty years ago.)

At an open-air market in Mexico this winter, I was approached by a Mayan couple who had a few jars of fresh pollen in hand. Not all Mayans speak Spanish, but these folks did, so I learned that the pollen was from the city of Merida. They had bought it from a beekeeper, repacked it, and wanted to sell a small jar to me for twenty dollars. Ten dollars. Five? They quickly bartered downwards while I waited silently in my wheelchair. I was impressed by their courage - they were wandering around the market, had no booth, so they could be evicted at any moment. They approached this Gringo in a wheelchair without apparent trepidation. I wish I could have helped them out, but I wouldn't take any raw food products from Mexico to Canada - raw bee pollen can carry exotic bee pathogens. I left them, but wanted to suggest they change their sales pitch. Not mention buying the pollen from a commercial beekeeper a hundred miles away. Without that honest information, a tourist such as I might imagine that they hand-picked the stuff themselves, in a forest where huge parrots and tiny monkeys watched them plucking the pollen from wild comb while killer Africanized bees hovered around their faces.