Welcome to The Bad Beekeeper's Blog

2008 Blog 2009 Blog 2010 Blog 2011 Blog 2012 Blog 2013 2014 Blog 2015 Blog

|

Candid Camera

We live close to the Rocky Mountains. One of our friends, Liz Goldie of Calgary, keeps some of her bees in an apiary in the foothills. As you can see in these pictures, our area is flush with interesting large animals. All the photos in this blog entry are Liz's pictures, used by permission. If you would like to re-post any of these, send a note to me first so we can see if permissions can be extended to your use. These pictures were taken with a Primos Truth Cam 46, a motion-sensitive camera with a flash.

This is one active beeyard! Part of the attraction is a salt lick, placed near the beeyard - it is set out for cattle, the wildlife are uninvited usurpers. Not surprisingly, the salt has the attention of the moose, but unexpectedly, grizzly bears are also tasting it. The bears have not noticed the bees, which are guarded by an electric fence, or they would certainly be rummaging through the hives. The photos are from this year, 2013, the oldest picture is the wolf in the snow, photographed in late April, and the most recent are the lions, from October 15, 2013. Mountain lions are relatively rare here, so this image of a mother teaching her almost-mature cubs how to keep bees is priceless.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What are these bees thinking?!?

A beekeeper in Winnipeg sent some photos of her hives. Her bees are misbeehaving. They broke cluster at minus 8 degrees (around 20 F), masses of bees are hanging out at the entrance, and she wants to know why. Sadly, unusually high numbers of dead bees are lying in the snow near her hives.

Here is the background: She has two colonies. Both were reasonably strong, but one, of course, was the star performer, the other just a bit weaker. Each were fed 25 kilos (55 pounds) of sugar dissolved in water in a thick solution. They also had autumn pollen supplements ten weeks ago. Mite counts were low and they were treated with formic acid in the early fall. They are queen-right and had a normal summer season.

I thought maybe skunks were the problem - or some other creature (or stress) was making the colonies come to the entrances and investigate. But when she sent the pictures I've posted here, I realized that's not it. The beekeeper is certain it is not a varmint (neither mouse, skunk, nor Winnie the Pooh or some other Winnipeg bear). The bees are guarded by fences and protected from the wind. Could it simply be that the bees became warm, are super-strong, and had to hang out? But then, why the dead near the entrance - and on the bottom board, as you see in the center photo below?

If you can guess why these winter-packed hives are suddenly hanging out like this on a cold wintery day, please send me a note.

|

|

|

|

Can Bees Smell Cancer?

This is an intriguing idea. A Portuguese designer has invented a novel system that might detect various illnesses, including tuberculosis, diabetes, and lung cancer. Susana Soares has built a lovely contraption - a glass bubble inside another bubble which holds a few well-educated honey bees and allows them to sniff out these diseases. Honey bees have an extremely keen sense of smell and they are quickly trained, Pavlov-dog style, being rewarded with sweets when they perform well. From the breath of a human with an affliction, disease is potentially revealed. It sounds odd, but a lot of things sound rather peculiar to me.

There is a British science firm, called Inscentinel, which is pioneering the research behind the device. A visit to their website is worth the look. There you will see honey bees locked in an Orwellian prison with their little heads poking out of tubes. Odors waft past and the bees are rewarded with a dab of sugar syrup. Within minutes the bees learn to expect the sugar-treat and upon smelling the training odor they immediately stick out their little tongues. When the bees encounter the scent again, they react with drooling expectation, tongues hopefully extended, indicating they have found diabetes-breath, or whatever they have been trained to detect. A clever idea, actually.

With the advent of the many honey bee health clinics around the world, this could possibly be an adjunct to other commonly offered bee therapies. In addition to honey massages and bee sting therapy, it may be possible to include screenings for sicknesses. Such a clinic would certainly be the right venue as honey bees would be involved in the clinician's routine anyway. Does it work? I don't know, but bees have extremely sensitive odor detectors, so perhaps it does. Is the system likely to be offered and developed? I'm not so sure as the training may be problematic. It is hard to make something like this transition into a practical application. But it is not impossible.

|

Deadly Truck Crash

One of the thousands of loads of bees heading south after the summer harvest didn't make it. On Sunday morning, November 3, a tire blow-out on a tractor-trailer caused this crash in Georgia that killed millions. Of bees, that is. No humans were hurt in the wreck. Each fall, commercial beekeepers pull their hives out of northern clover fields and send them southbound where they can winter more easily in balmy Florida - and maybe make a bit of orange blossom honey in late winter. Semi-trucks can haul about 400 double-story hives, each with perhaps 30,000 bees in late fall. That's 12 million bees and it is just the tiniest droplet in the river of hives (some 500,000 colonies) that are trucked to warmer climates in Florida, Georgia, Texas, and various other mild locations - every fall. The hives come from pollination and honey production in Maine or New York, Wisconsin or the Dakotas. This is in addition to hundreds of thousands of colonies moved into California each season.

This accident is a tragedy for the bees, and for the beekeeper. It is hard to recover from a mess like this. Even if there is insurance (usually there is not) it only pays for a small portion of the damaged equipment, not lost production from future queen sales, honey production, or pollination fees. I don't know who owns the bees (hopefully not one of my relatives), but this accident reminds me of the close calls I had trucking bees when I was a youngster. For about ten years, I hauled around 1,000 colonies a season south on my own truck. I was more lucky than careful and never had an accident that hurt anyone or any bees. But I could have - driving bees is risky business. The bees need to arrive quickly, so the beekeeper-driver is likely to sit behind the wheel too many hours. These days, more and more beekeepers hire professional drivers with big flatbed rigs. Beekeepers provide the netting and the forklifts on both ends of the trip for loading and off-loading. But it is still quite a difficult logistics project.

|

Bees Delivering Pesticides

This sounds so bizarre. At first. Canadian researchers have found an odd way to potentially deliver benevolent viruses, fungi, and bacteria to greenhouse vegetables. Before some lucky bees are allowed to fly inside glasshouses to pollinate peppers and cukes, they trudge across a little tray laced with organics that greenhouse growers would otherwise spray in their shops. The materials are hopefully harmless to bees, and well, since they are going to visit flowers anyway... It's a bit like carrying the garbage out to the black bin as you leave the house for a morning jog. Or a bit like using viruses to carry meds to kill cancer cells. In the latter case, the virus is called a vector. In the greenhouse case, the insects are called bee vectors. There is even a company, Bee Vectoring Technology in Brampton, Ontario, which has developed a technique to do this.

A company called Bee Vectoring Technology was apparently started to find ways to use bees to deliver organic pesticides, which are naturally occurring killers that should allow farmers to sell the resulting vegetables as organically produced food. In a "forward-looking statement" related to the acquisition of Bee Vectoring Technology by CT, a "capital pool company", the following is announced:

BVT and its scientific team have developed a globally patented bee vectoring technology;

using bees to deliver commonly found organic fungi to flowering plants, acting as an organic

pesticide as well as a fertilizer, all without water. The technology has been tested on

and has been proven to effectively and organically control harmful diseases affecting

important crops such as sunflowers, canola, strawberries, raspberries, pears, tomatoes,

blueberries, almonds, peppers, eggplant, pumpkins, various melons, kiwi, apples and coffee,

among others.

Let's take a close look at this statement. I deeply apologize and will immediately retract what I am writing if I have missed something here, but the entire paragraph makes no sense to me. At all. First, there is no such thing as a global patent. Each country (even North Korea, where the Dear Leader is Supreme Inventor) has its own system and if you invent something in Canada, you will need to apply for patents everywhere else. But, by the way, how does one patent the idea of forcing bees to trudge through gunk? Bee researchers at Guelph have been experimenting with bee vectors for years, so they should have precedence for the idea - as some US companies would as well. Next, how does "an organic pesticide" act as a fertilizer? Potash? Nitrogen? Sorry, I don't get this, either. Next, the "technology has been...proven to effectively and organically control harmful diseases..." Harmful diseases? A disease such as an aphid or whitefly? Sorry, those are not diseases, we are talking about delivering a pesticide to attack pests. Then, the list of plants. Did the company test their "globally patented" system on kiwis and coffee? Or do they otherwise somehow know that the technology works on "diseases" affecting these crops, "among others." I went to the company's website, clicked on their link for case studies, but it is written (at the time of this blog) in the Lorem ipsum language, which I don't read very well. Allow me to quote, maybe you can understand this: "Sed auctor, sem et volutpat facilisis, risus leo venenatis leo, ultricies accumsan urna ante vel nisl." That's their case study about strawberries. (There's more, you can go to the site and read the rest.)

Their information also states bees among sunflowers at a density of one colony per three acres (costing $43 per acre) increases commercial seed production - from 1,600 pounds per acre to 2,400 pounds (adding a value of $184 per acre). This may be true - pollination economically increases yield, as farmers have understood for at least a century. But the statement seems totally out of place, perhaps even implying that bees carrying pesticides on their tiny feet are the reason for the dramatic increase in farmers' income. There are also statements around how the bees' activity of delivering "Vectorite," the carrying compound, plus the "selected bio control agent" acts as both "a pesticide eliminating disease, and a fertilizer, increasing yield." Of course yield is increased - but I've never heard anyone call pollination by bees "fertilizer." Unless there is some mysterious fertilizer in the Beauveria bassiana being applied to the flower stigmas. The system described for delivering bees to farmers is to take beehives with "300 bees per hive" to farmers' fields at a density of one hive per acre. 300 bees per hive? They probably mean 50,000 bees per hive if they are talking about honey bees among sunflowers, which is what farmers rent for pollination. If they mean bumblebees, then they are not talking about delivering hives, but nests, and they will need more than one or two or even ten or twelve per acre. Bee Vectoring Technology and its new owners may be on to something really good, helpful, useful, and economically viable, but their information should have been reviewed more carefully before it was published.

So far the bees have been delivering Beauveria bassiana, a fungus that kills nasties like whiteflies, aphids and Lygus. And termites, bed bugs, mosquitos, various beetles, and thrips. And who knows what else? And, if the naturally occurring fungus isn't tough enough, there is the GMO variety that could be applied to the bees' knees. Unfortunately, a genetically modified version of the Beauveria bassiana fungus has escaped (or "leaked," as they say) beyond its confinement area near a Christchurch university in New Zealand, much to the chagrin of the government and local farmers. I am not saying that the escaped GMO fungus is a bad thing. I'm just saying it escaped.

Where does this put us in this saga of bee vectors? Honey bees (and presumably bumblebees) can be forced to slug through natural (or GMO-modified?) fungi flakes which will stick to their paws and then get rubbed on flowers when the bees go about their pollination business. Sounds like an effective use of the bees' energy. The stuff they carry can kill aphids, beetles, flies, and other creepies, but not hurt the bees. (I'm not sure why the bees are safe.) The farmers and greenhouse people can use fewer pesticides - instead of fogging the entire building or field, just the plants' flowers are affected. That's definitely a good thing. How does the public perceive the idea? Very well, it seems. CBC Windsor has an article about this research with a readers' poll attached to the bottom. Exactly 2/3 of the 2,000 who have voted so far support the idea of bee vectors.

|

Should Prince Charles be king? Or should he be a beekeeper?

I am one of the few people I know who has taken a personal public vow of allegiance to the Queen. And all her heirs. I take my duties seriously. It is my job to offer helpful life skills to the Family whenever I should. That's the price of loyalty. And Canadian citizenship, for immigrants. Although I pledged my allegiance twenty years ago, I suspect it is still in effect. So here comes my advice to one of her majesty's heirs, the Prince of Wales, the reluctant future king, Charles.

I would probably get along with the guy. He seems gangly and clumsy, like me. And he likes bees, also like me. Well, that's perhaps the limit of our similarities. But I can still contribute a few words regarding his appearance on the front page of this week's Time magazine. In a corollary net article, Born to Be King, But Aiming Higher, author Catherine Mayer tells us why we should all appreciate this man. Mayer "found a man not, as caricatured, itching to ascend the throne, but impatient to get as much done as possible before, in the words of one member of his household, “the prison shades” close. The Queen, at 87, is scaling back her work, and the Prince is taking up the slack, to the potential detriment of his network of charities, initiatives and causes." The future prison of being reigning monarch is what caught the world's attention, not the fact that Prince Charles has devoted over 35 years to the 20 charities he formed, almost all centered on preserving the environment.

I don't agree with each and every charity Prince Charles supports (and/or created). But rather than waiting around to inherit a job (Who on Earth does that anymore?), the prince decided to see if he could stay busy making a positive difference. He hasn't been racing fast cars or buffing his abs on the beach. There is apparently no misspent youth. Instead, he raises some hundred million pounds each year and directs the expenditures. Those grants go to "Sustainability, Rain Forests, Youth Programs, and Environment," according to Prince Charles' own website.

So, here is my advice. On the off-chance Charles should outlive his mother, (Or, "Mummy" as he infamously called the Queen at her 75th birthday gala.), he should simply pass on the king thing. Plenty of lesser monarchs have tossed the crown for frivolous reasons. Prince Charles has his work already, and it needs him. And he has those bees behind his Clarence House residence. Why be king when you can keep bees?

The Prince's House - and his Bees

|

Friends bought a chocolate bar for me. Not just any bit of chocolate, of course. They were in eastern Europe and the stuff they found was really interesting. It contained propolis. And tasted like it. Eating chocolate-propolis is not for the faint-hearted. I liked it, but this particular bar was only 5% propolis - and I have been known to chomp on raw 100% pure bee glue in the bee yard. Propolis is resin from trees, collected by honey bees, dried a bit, and stuck around the hive by the bugs as part of their nationwide preventive health care program. It contains a lot of natural antibiotic properties - it kills germs, and the bees know it. So they coat crevices and untidy hollows with the goo, using the antibiotics to keep biotics away from the nest. The bees have also discovered that propolis is a great sealant. Just as our own ancestors learned to make tar from pines to seal leaky boats, the ancient honey bees discovered they can plug holes that would sink their winter plans by exposing a colony to wind and snow.

Bees can be encouraged to collect propolis if you are sloppy with bee box placement - placing supers askew (as many clueless ex-employees have done) forces the bees to jam the gaps with fresh propolis. A few companies sell gadgets that can be plopped atop the hive skyscraper in lieu of a lid - again giving the bored bees something to fetch and paste into the hive. The beekeeper scrapes the propolis off the offending hive parts (presumably using a sterilized stainless steel propolis scratcher) and carries the meds back to the shop where alchemists dice it and blend it with chocolate for future fine dining.

The company that makes this chocopropo bar, KÕLLESTE KOMMIMEISTRID, is in Estonia, a tiny country bordering on Latvia and Russia and sitting close to Finland and Sweden. The last big thing to come out of Estonia (before this propolis candy) was

I was curious about the factory making this chocolate bar, so I traced them online. They claim to be the first and only company in the world that figured out you can mix propolis with chocolate and make candy. This of course is ridiculous. Even I made and sold a similar product years ago. It is not a new idea, nor unique. A quick on-line search turned up a number of companies making the stuff, most probably predating the 2006 start-up of Kõlleste. There even appears to be a competitor in Estonia. Nevertheless, the company's web site claims they are the inventors and have (they say) two patents, one for adding propolis to chocolate and the other for adding pollen. Surely they jest.

"WE ARRIVED AT THE IDEA TO MIX POLLEN, PROPOLIS AND BEEBREAD

WITH CHOCOLATE IN ORDER TO BALANCE THE TASTES AND MAKE THE

HEALTH-GIVING SUBSTANCES PLEASANT FOR EVERYBODY. IN THE

PROCESS OF DEFENDING THIS IDEA, IT WAS DISCOVERED THAT SUCH

APPLICATION IS UNPRECEDENTED IN THE WORLD.

TODAY, KÕLLESTE KOMMIMEISTRID HOLDS 2 PATENTS:

USE OF POLLEN IN CHOCOLATE CANDY/BARS FROM 5% TO 70%

AND USE OF PROPOLIS FROM 2% TO 50%."

The idea that something as simple as mixing two ingredients should be awarded a patent is strange and would be difficult to defend in any court. Sometimes patents are abused by companies that do not have rights (although it could be that some Estonian patent clerk actually granted a certificate to this outfit). Even worse, companies may claim patents years after they have expired. This is somewhat common and can lead to incredibly huge fines, in the USA, at least. It is against the law to place a patent number on any item sold after the patent is expired. The law exists to stop outfits from intimidating competitors after the patent has expired. The fine is severe - $500 for each and every item sold that has ax expired patent number on it. Even big companies are guilty - major pharmaceuticals were fined millions of dollars for printing "US Patent Number 1234567890" (using the actual expired patent number) on bottles of a common pain killer. If you manufacture any neat little beekeeping product and have a "US Patent" stamp on it, you are libel for the same $500 per item sold if your beekeeping gizmo's patent is expired. That's $500 per item - sell ten expired patent hive covers, for example, and pay $5000 in fines - if you still have the patent number on it. Sounds brutal, but the idea is to prevent extended monopolies. Free the technology for the next entrepreneur. Obviously, I am only giving American laws here - you can read about it in this Wall Street Journal newspaper article. It is entirely possible that in Estonia, mixing chocolate and propolis can be patented. But the company would also have to try to file patents in each country where it hopes to have exclusive rights - including Australia, Serbia, Italy, Brazil, the USA, and a whole bunch others where chocolate and propolis have already met.

About that chocopropo bar... Did I mention it is good? Better than any propolis I'd ever nibbled in the bee yard.

|

|

It's easy to know a lot these days. But being smart is quite another thing. It can't be bought or taught. Not the way facts are. The internet is the reason knowing things is all rather easy. I research for my work every day and it amazes me how much information is on the net. I don't mean all the great conspiracy theory pages and gossip - that's entertainment, not information. By the way, did you know that the scientist who has the cure for cancer that the government won't let you use learned everything from aliens caged up in Roswell, New Mexico? Their spaceship crashed because Eisenhower was secretly sending low-frequency vibrations through the atmosphere so Americans would be brain-washed into thinking that jet vapour trails are harmless while they are actually seeding a genetically modified ragwort that gives off pollen that makes people have fewer children. All this is top-secret, which is why you can only learn it from the internet. But that's not the sort of information I was talking about.

There are sources that are more reliable. I was directed to a great website recently that is trying to gather various scholarly 'open-access' repositories in a convenient place. This is onlineschools.org and their list appears on a page they are calling Open Access Journals. From this jumping-off spot you can access Oxford University scientific papers or Wiley's abstracts, for example. This is a fantastic resource for the millions of us not directly connected to a university who still need peer-reviewed materials for research and writing. As a tiny example, last week I wrote a bit on this blog about the first beekeeping book, written by Reverend Charles Butler. One can go to Wikipaedia and get peer-edited information, much of it good. But keep in mind that not all writers at Wiki are as conscientious as my 11-year-old son, who has been a wiki-editor for two years. He looks for multiple sources before editing and is unbiased in his entries. Not all of Wikipaedia's editors are as careful and trustworthy. So, it pays to dig deeper and uncover source materials. If you go to Open Access Journals, you will find a link to JSTOR, a non-profit service set up almost 20 years ago to support libraries. JSTOR scans millions of pages a year, keeps them on-line, and allows humbles like you and me to obtain a free account and access 1,300 different journals - hundreds of thousands of articles. You can't download them, but you can read the papers while logged in. Powerful for peasant researchers. Regarding beekeeper Charles Butler, among the papers I read on JSTOR was one written by a historian in 1943 and originally published by the University of Chicago Press. It has information I've not seen before - because no library in Calgary has a 1943 copy of that journal.

But even science journals and scientists can make ugly self-serving gaffes. Remember Andrew Wakefield, accused of falsifying links between immunization shots and autism - resulting in the spread of devastating childhood illnesses (measles, mumps, rubella) while autism nevertheless developed in non-vaccinated kids. Yes, Wakefield was peer-reviewed, but his work never passed the smell test. And that's the part you can't get from the internet - that's the part that you have to bring into your research yourself. It takes critical thinking, not just knowledge, or you will be like someone I know who has been telling Facebook buddies about mysterious top-secret atmosphere vibrations that are government experiments to do something evil to its citizens. Sadly, we have entered an age when people believe they know things, but don't bother to think - or at least double-check facts. That's the element that can't be bought or taught.

|

Forget Steve Jobs and all that i-stuff. If you want to talk about design that trumps utility, then look at what Tamara Mihajlović and her co-designer Njegos Lakic Tajsic have created. This is magic. A brilliant honey container like none we've ever seen. Crystal-shaped, with a pyramid of honeycomb in the centre (maybe made of plastic?) it is a bright and unique way to showcase honey. Some describe it in crunchy words like "organic, crystalline, and rock-like" while others just gaze at in awe. Why did no one else think beyond dull boring glass jars and cutesy squeeze bears? This honey container is elegant, gorgeous, and totally impractical.

A pair of Serbian designers created this container as a graphic arts project, then made up a fictitious company (BEEloved Honey) to pretend to sell their beloved honey. But would anyone actually buy non-existent honey, if not for the gorgeous bottle? Certainly, I would, if I had a few thousand pounds of honey to market through gift and gourmet stores. And it would support an enterprising young couturier. Tamara Mihajlović is a 23-year-old Belgrade graphic artist studying at her university's faculty of Art and Design. She has also been art director and a technical editor for Politikolog, a local political journal. Her other recent creations include a series of anti-Aids posters and music festival ads.

|

Of course it's impractical. Granulated honey will stick to the wee little crevices and refuse to exit the bung. But that could be resolved with a quick dunk in a hot bath. Besides, the combo honey and jar looks too good to open and eat, so it is likely to remain corked on a granite countertop for years. A bigger problem is that no one will likely bother to adapt an automated packing line that could fill 5,000 of these odd-shaped bottles in a day. But that's not the place such a container should be used. Instead, I can imagine a thousand artisanal honey makers filling a hundred of these lovely packages over a couple of weekends in their tiny shops. Then they would retail their honey in Tamara's classy container at gift shops. No Walmarts, Walgreens, or Krogers for these beauties.

If you own a little honey house tucked in a woods, you might be wondering where you can order these lovely containers. Alas, you can't. Not yet, anyway. Mihajlović and Tajsic are still seeking a company willing to manufacture these honey bottles. If you are that adventurous bottle-maker, this might be the i-jar you've been waiting for.

|

Democracies often work better than dictatorships. Democracy is based on crowd decisions, or, in the trendy new parlance, crowd sourcing. Crowd sourcing really came of age with the internet - put your question, issue, project, or some politician's dirty laundry on the internet and wait for the responses. (If you are wondering about this site, I set it up without instant crowd feedback, but you can write to me any time at miksha@shaw.ca.) We like to think The Wisdom of Crowds,

as one book calls it, is a new development. But our indefatigable honey bees have been group-thinking for millions of years.

Who, among the colony, decides where a swarm will settle? Four hundred years ago, the answer was "That big bee over there, see him? The King. He decides." (It was the great Greek philosopher Aristotle who first declared the hive was ruled by a king bee. His mistake lasted 2,000 years. By the way, Aristotle noticed that the queen, i.e., his king, has a stinger which, in his logic, meant it was a male.) An English pastor, Charles Butler, realized the king is the queen and wrote about it in 1609 in the Feminine Monarchie, the first English language beekeeping guide, a book that went into five editions and dozens of printings. He imagined she is an Amazonian, a strong and fearless female similar to Queen Elizabeth, his patron a few years before Feminine Monarchie was written. So, is it the queen who makes important decisions in the hive?

Wrong again. The queen is not a leader, she is just a hapless overgrown egg factory, and one of the most helpless of the bees in the colony. The real leader is a worker bee named Betty Sue. She calls all the shots. She decides when to swarm and where to settle, among many other things. Lucky for the bees, there is more than one Betty Sue in each hive. Tom Seeley, in his excellent Honeybee Democracy,

explains that beehive group-think results in better choices than any single individual Betty Sue might make on her own. According to Seeley, about 3% of a colony's members are actually involved in the scouting and decision making, but that means over 1,000 bees are in that clique. This creates a lot of varied perspectives, observers, and decision-makers. Once that sub-group resolves a choice, those Betty Sue clones will buzz, shake, and rattle their compatriots into also agreeing and then venturing off to the new nest site. Apparently, witnessed by their survival since the Cretaceous, honey bees have used this as their successful ploy for a very long time.

Contrast this with what Henry David Thoreau essayed about humans in 1838: "The mass never comes up to the standard of its best member, but on the contrary, degrades itself to a level with its lowest." That might be true among television viewers, but when working with large groups of people tasked with contributing to a project - and given a democratic opportunity to question and revise the work of others - the cumulative result is better than the achievement almost any single contributor could have produced. In The Wisdom of Crowds, author James Surowiecki uses an example of a jar of jelly beans and a classroom of bean counters. The class submits a secret ballot - guessing the number of beans in the jar - and the average of the group (for groups over twenty or so) is always better than the worst guesses made. And usually better than the best guess. Contrary to Thoreau, the mass is not degraded to the lowest member's level.

|

Ted. He talks and talks and talks. Maybe you know Ted. TED, actually with capital letters, stands for Technology, Entertainment, Design, and the TED Talks are a series of conferences with great (entertaining) speakers. The talks are filmed and then loaded to the TED Talks website, which has over 1,500 talks (by speakers such as Bill Clinton, Bill Gates, Jane Goodall, Richard Dawkins, and a number of Nobel Prize winners) where anyone can watch them for free. Actually, the non-profit, Sapling Foundation, that hosts TED talks has released the talks into the Creative Commons, making them available for public use with a few restrictions.

You can see a really great TED Talk by Marla Spivak, one of the smartest of all bee researchers, at this link. Her 15-minute TED Talk lists three or four reasons bee colonies die off. Two of her explanations are basically aspects of the same thing - fundamental changes in agriculture, the other two are chemicals and pests.

So, here is a bit more detail on Marla Spivak's list of the killers of bees. Very briefly (please watch her short video, Marla is a great speaker), the culprits are 1) diseases and pests - especially varroa mites, for transferring viruses and for beeing the bloodsuckers they are; 2) monoculture, which includes the collapse of the family farm and the loss of natural habitat, and has created 'food deserts' where only one meal is served (at most) for just a few weeks of the year; and, 3) chemicals, including insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, and the break-down chemical compounds of these complex molecules. You can see these are inter-related. Farming changed, leading to huge efficient monoculture enterprises where pests proliferate unless controlled by chemicals while varroa weakens the bees so they are more vulnerable to the problems brought by chemicals and poor nutrition. The result? Not so good for honey bees.

|

Dutch bee hives in Manhattan? Of course. Four hundred years and counting. New York was known as New Amsterdam by its first settlers, the Dutch from Holland who arrived on lower Manhattan Island in 1614. That's even before the Pilgrims hit the rocks in Massachusetts. New Amsterdam was the capital of New Netherlands and once claimed all of present-day New Jersey, Maryland, and Delaware, as well as much of New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. It was funded by the Dutch West India Company which had built settlements all over the world. The Dutch thought they'd enter the fur trade, but failed to grow their Manhattan city enough to keep ahead of the English who swooped down from New England, defeating the Dutch in the Battle of Wall Street, around 1665. The English gained control of beehives that the Dutch had brought across the Atlantic as early as 1616 or so. By then, those bees had made The Island their home for fifty years.

I am writing about this because I saw a story that got me thinking about how bees ended up in America. I'm linking to the story about some Dutch bee boxes that were noticed by Irene Plagianos, a Manhattan writer reporting from the NYC financial district. The photos of those hives, which you can view in a 'slide show' by jumping to this link, shows brightly coloured equipment and happy Manhattan beekeepers.

Dutch bees in Manhattan? Honey bees are an invasive species. I sometimes tire of beekeepers who claim to be 'natural beekeepers.' These are the folks who drive their natural SUVs out to their natural hives every weekend, light a natural steel-bodied smoker, open the hive with a natural metal hive tool and manipulate the natural top-bar frames made from western pine or southern cypress. Then they manipulate the invasive insects which were hauled into North and South America, Asia, Australia, and the Pacific Islands by boat a few hundred years ago. I doubt that many who belly-hoot the merits of their natural beekeeping realize that all beekeeping is unnatural. Attend bee meetings and bragging about natural beekeeping is committing any oxymoron. Honey bees are not natural in most parts of the world. And beekeeping - keeping bees in houses of human design - is not natural anywhere. Robbing bee trees, perhaps, but not beekeeping.

Who's calling Who an invasive species? Whether you believe humans walked out of Africa or were chased out of Eden, either way we have done a pretty decent job of populating the planet. A frighteningly decent job. From creationists' estimates of 2 originals (or from some evolutionists' estimates of 10,000 people during our 'bottleneck years') we now number 7,000,000,000 and have set up tents almost everywhere. (Congratulations, humans.)

What do I think? Humans, the invasive species, has introduced honey bees, another invasive species. We've also transplanted apples and alfalfa and almonds and a thousand other things from other parts of the world. It's what we do. What would Italian cooking be without South America's gift of tomatoes? Or Montana honey without European bees and Asian sweet clover? As we go about the practical business of feeding seven billion souls, we have to do some unnatural things. I'd rather have the world functioning as it does than to role back to the time when Eve's children were not reaching their 35th birthday and most children died in their first year. People live much longer and much healthier lives under this new, unnatural system. Undoubtedly, we have a lot of mess to clean up. We need strongly enforced laws around pollution and pesticides. But little of what we do with our bees is particularly natural. But that's not a bad thing.

|

You can be one of the smartest economists in the world, and still not realize beekeeping is a lousy investment. The celebrated author and public speaker, Gary Shilling, who writes for The New York Times, Forbes, and The Wall Street Journal, and has apparently had a British coin named after him, nevertheless persists in keeping bees in his New Jersey back yard. A news team landed in his apiary and reported "It's An Awful Lot Of Work To Raise Honey Bees In A New Jersey Backyard." I imagine it's also an awful lot of work writing for the Wall Street Journal, too.

This guy, by the way, is a real beekeeper. The video news clip from Business Insider begins with Mr Shilling mixing something in a five-gallon bucket, workshop door wide open, and equipment stacked all over the place. Then it shows him igniting his smoker with a wildly flaming blow torch. Love the enthusiasm. The camera next swings up to his bee yard with a gorgeous shot of the hives, stacked higher than a basketball player and painted camouflage green. Except for some nasty creepy crawlers on the bottom board, things are neat and tidy. OK, maybe he is not a real beekeeper - things are too neat and tidy.

Does Shilling find beekeeping easy? After describing how the 85-pound boxes keep his tummy muscles in shape, he goes on the say that beekeeping is amazingly intellectually challenging. But you knew that already. What does Gary Shilling do with his 4,000 pounds of honey each year? He could probably retail it for $30,000, but he gives it away instead. Now I'm not so sure he's an economist.

|

A bee-kill decision in Florida. According to The Ledger, beekeepers Barry Hart and Randall Foti lost $390,000 worth of bees and honey production when one of Florida's largest citrus producers sprayed pesticides. (The loss does not seem exaggerated. For example, Foti's honey production was off by 200 drums of orange blossom honey and millions of dead bees were piled in front of his hives.) According to a Florida state investigation, the spraying was illegal. The grower, Ben Hill Griffin Inc, was ordered to pay a fine. Of $1,500. That's the fine?? Destroy two beekeepers, pay $1,500? It would be bad enough if the pesticide use had been legal and all those bees were killed. But $1,500 for an illegal application of poison resulting in this sort of damage? This sends the signal that one might spray whenever and however it best suits the grower, then shell out the trivial fine. The state pointed out that the maximum fine is $10,000 per instance of abuse. The state says pesticide laws were violated by Ben Hill Griffin Inc on February 21, February 22, March 8, and March 19. That would sort of indicate four violations and up to $40,000 in fines. According to one of the beekeepers, Randall Foti, every four days they were spraying where his bees were working. The insecticide application occurred while the orange trees were in full bloom. Millions of bees died.

This is all very interesting, but, as it turns out, there is much more to this story. The company accused of using the pesticides is a green, natural citrus grower, indicates Florida's Natural Growers, a marketing cooperative. The fellow in charge is a fourth-generation grower - apparently a gentleman with a deep love for the environment, for the aquifer, for wildlife. According to Florida's Natural website, the groves' operator, Ben Hill Griffin IV, "prides his grove operation on environmental stewardship, as it helps to recharge the aquifer, generate oxygen, and provide a home for an abundance of wildlife. Many of the family's decisions in the groves are made to accommodate both the health of the citrus trees and the land they grow from." I could almost hear frogs croaking and birds tweeting as I read about the way oranges are grown by Ben Hill Griffin Inc. What I read were all very nice words and who can doubt what Florida's Natural Co-op says? Certainly not I. So, I wrote to Florida's Natural and asked how the company that stands accused by the state of Florida (and is ordered to pay the pittance of a fine) fits with the Florida's Natural brand. Natural, right? If they write back, I'll amend this blog entry with their information.

In reading the family biography and the Ben Hill Griffin company details on the Florida's Natural website, I felt compassion for the corporation. They love the land. They must be heart-broken about the tragedy they have apparently caused. They have a fleet of pickup trucks painted in "Griffin Green." Green. The clean color. The present owner started in the family business at age 11, "working with the baby trees in the family nursery." Sigh. But Ben Hill Griffin Inc is a huge corporation. The University of Florida's football stadium is named after the founder of that huge corporation. Ben Hill Griffin Jr, now deceased, was majority share holder of a company that owned the land the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad was built on - and various sugarcane, citrus, cattle, forestry, and sod farms. He was on the Forbes List of richest Americans. When he died, his $300,000,000 estate was bitterly contested in court by his four daughters who seemed to feel the one son (Ben Hill Griffin III), who was the sole trustee, had grabbed the bulk of the money, according to the Orlando Sentinel. In the newspaper's story "Drama Ends With Heirs Splitting Citrus Millions," they describe the fight as tabloid stuff: "The closet door swung open and out fell the skeletons..." This is not your average grove-owning family. Among Griffin Jr's grandchildren are several Republican politicians - you might remember Katherine Harris, a Griffin granddaughter, who was Florida Secretary of State in 2000 when the 'hanging chad' issue contributed to George Bush's election. Other members of the family have been in the Florida Senate and House. This is a powerful family. So it is really reassuring that their company is so anxious to do good things for the environment.

Beekeeper Foti has said that he saw empty containers of Montana 2F insecticide in a burn pile in the groves. If this is true, what does it say about one's love for aquifers, the land, the wildlife? Or maybe empty canisters of Imidacloprid stacked in a burning pile are OK? I have read Montana 2F's label. Surprisingly, yes, old containers may be burned if so allowed by the state, but the label also warns: "If burned, stay out of the smoke." Always good advice. Stay out of the smoke. The label also says:

"This product is highly toxic to bees exposed to direct treatment or residues

on blooming crops or weeds. Do not apply this product or allow it to drift

to blooming crops or weeds if bees are visiting the treatment area.

This product is toxic to wildlife and highly toxic to aquatic invertebrates."

In issuing its fine the Florida regulators also said that in using insecticides, "The label is the law."

Does this remind you of Hitchcock's Birds? According to this Metro news story, a Driver's Ed instructor and two students were trapped in his car until fire fighters were called to pressure-wash the car. I suppose the bees were killed from all that blasted water. This is just one of the ways China's rapid industrialization is wreaking havoc on the environment. This decade, it is one car and one swarm. Next decade, it might be two swarms. And then what? Three? Four? As I read recently in the Economist, people all over the world want to share in the West's consumptive, gluttonous habits. So expect more of this.

|

Road kill. In this case, it's bees. I was out of the city yesterday, cruising the Alberta back roads at 110. (The posted speed limit was 100, so maybe that was really my speed.) I passed a few bee yards tucked into meadows within small groves of trees. On one moderately busy paved road three honey bees spit up on my windshield. Big blobs of nectar were the imprint on the glass where those unfortunate bugs made contact with my van. I spent the rest of my trip calculating how much money this collision cost the beekeeper in lost honey. Not much, it turns out. But I wasn't the only traveler out there.

How many bees does it take to make a dollar? These days, a dollar's worth of honey (wholesale) is about half a pound. Well, those hapless bees that damaged my windshield were fat, but there certainly was not half a pound of nectar among the lot. And nectar cures into honey at a pretty high ratio. So we are talking partial pennies, of course. (Canada ridded herself of whole penny months ago.) The math (and the guilt of ending three promising foraging careers) was making it hard for me to think about my driving, so I decided to look at this in a different way. Yesterday, about two cars a minute passed that bee yard at the same speed as my van - or faster. (Alberta's farmers drive quickly - their grandparents all raced horses at one time or other.) At a rate of two vehicles per minute, that's 30 each hour. If, like my van, they each kill three bees, then we've killed almost a hundred bees. That would be a thousand in the course of each of our very long, very sunny summer days. Over a period of thirty days of peak honey flow, that amounts to 30,000 dead honey bees. This is just an estimate, but it represents something close to half the foraging population of a producing hive for the month. The average crop here is 200 pounds, so the beekeeper - over the course of his season - has lost about 100 pounds of honey, or 5 pounds from each of the 20 colonies in that apiary. One hundred pounds of honey, at today's prices, is $200. That's something to notice. And, five kilometres down the road was another yard and another honey bee slaughter site.

What's the solution? Always a believer in the benevolence of a big cumbersome government, I could advocate for highway signs and strict enforcement. Why allow drivers to speed along at 110 when there are bees at play? We should have heavy fines for offenders. Or, perhaps we could have police checkpoints where kindly RCMP officers scrape windshields or otherwise count the road kill and drivers then pay a fee, especially if they've been killing without a license. To be effective, the fee would be much greater than the pittance of lost honey from the few bees clobbered - a prohibitive penalty, if you like. Then there is the libertarian's perspective. The government stays out of this particular issue. The marketplace takes over. Honey prices soar because of the reduced crop. Or beekeepers, counting all those partial pennies lost, simply move their bees to safer spots.

There is some good news in this story. The squashed bees on my messy windshield indicate the Alberta honey flow (at least in our area) isn't over yet. And with the forecast predicting warm sunny weather, maybe it will last into September.

|

Chinook Honey Farm's Honey Harvest Festival was today, near Okotoks, just south of Calgary. As always, Art and Cherie entertained their hundreds of guests with lots of games, demonstrations, and programs. The farm has a great meadery with a wide variety of excellent honey wines which I think they've been making for at least five years now. But it is also a fully functioning commercial honey farm with an interesting visitor centre/store.

We try not to miss the various Chinook Honey festivals. Something new for this year's Honey Festival was a bee-beard demonstration. Select souls donned a few thousand bees, partly to prove that bees are not vicious savages, and partly to prove it can be done. In this case, the bearded folks were able to grow full-length whiskers in the Abe Lincoln style. Not all bee-bearded wannabees are so lucky, as we've seen with 34-year-old Matthew Cruikshank of Burlington, Vermont. The poor chap has been trying for years - as you can see in this national web magazine's article: "Man Has Trouble Growing Full Beard of Bees." Fortunately, the participants at this year's event didn't have such problems.

Finally, what bee event would be complete without a donkey or two dressed up as a bee? My kids found Bee-ore, the reluctant worker donkey-bee, to be a docile self-effacing creature. No rides, fortunately, but plenty of delicate nose rubs.

|

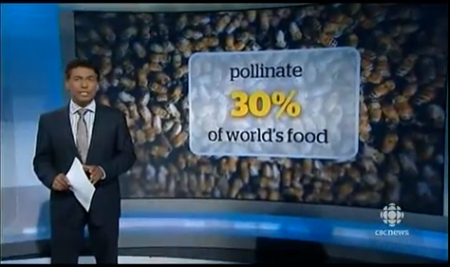

CBC Evening News Blames Neonics for Colony Collapse... In a touching - and sad - news program from CBC's National, we see the story of an Ontario beekeeper who is losing his bees. View the complete video on YouTube.

CBC News seems convinced that neonicotinoids are killing bees. Quite likely. Pesticides kill insects. Bees are insects and neonics are insecticides. Bayer, the makers of the stuff, dares to offer a differing opinion. It is unfortunate that neonics, as neonicotinoids are sometimes called by the spelling-impaired, are implicated in honey bee deaths. Unfortunate because it wasn't supposed to turn out that way. Neonics were designed to be less environmentally harsh and were expected to replace the much more damaging families of organophosphates and carbamates that can be pretty indiscriminate in their slaughter sessions. Neonics are applied mostly to corn, rice, potatoes, and canola. (It is also applied in lesser quantities on a host of other crops.) Of those crops (corn, rice, potatoes, and canola), only canola is visited by honey bees as a foraging source. Southern Alberta has hundreds of thousands of acres of canola, and bees are rented by the tens of thousands for canola pollination. Neonictinoids are used here. But we have not seen the bee deaths described by others. The same might be said for Australia, which has apparently not yet experienced colony collapse disorder and has had neonic usage by the millions of kilos for years. Other places - Scotland and British Columbia come to mind - have either banned neonicotinoids or use them very sparingly, but CCD is still a big problem.

I am NOT saying neonics are OK. They are pesticides. They kill chewing and sucking insects. And, as I've heard some beekeepers say, bees suck. They can't help but be hurt by neonictinoids. But does the stuff cause CCD? Not likely. If you watch the video that I've linked above, you will certainly have great sympathy for the beekeeper and his wife and six kids, living in their apartment above their honey extracting plant. The man is working hard and his losses are real. But we need to consider all possible culprits for his business's demise. As a mathematician and scientist, I get irritated when I hear generalized statements like some of those in this news clip. It is stated that 85% of the dead bees in the apiary shown had neonic residue. Well, 100% of the bees had wings. Correlations do not guarantee causation.

|

Bees have made the cover of Time. Missing bees, that is. The cover announces "A World without Bees" and promises to disclose "the price we'll pay" if we can't stop the bee losses. I'm not sure exactly what triggered this week's special coverage - bees have been vanishing off-and-on for at least a century. My father - a commercial beekeeper in Pennsylvania - told me about his spring of '52 when every time he opened a hive there were fewer bees in it. He called it "No-See-'em Disease," which he said meant the bees simply disappeared. You didn't see 'em. The colonies had good queens, lots of healthy brood and honey, but the adult populations dwindled. Others had seen similar things happening. The cause was never determined. This sort of thing has been going on for a long time.

Back in 1900, most farmers - or their neighbours - had a few colonies of bees. In the USA, there were an estimated 10 million kept hives. By 1950, there were 6 million. Today, there are about 2.4 million colonies of bees. What happened to all those disappearing bees? Most kept hives became unkept when farms increased in size and farmers simply didn't want to mess with stingers and honey anymore.

Particularly interesting statistics come from Oklahoma. The state had 60,000 colonies of bees in 1978; 10,000 in 1988; 3,000 today. Over those 35 years, agriculture was flipped on its head in that state. Oklahoma's small farmers were gobbled up like turkey feed. Fewer farm families; fewer bees on family farms. This has been repeated throughout the industrialized world - Germany, France, eastern Canada, Japan, and of course, most of the USA. Meanwhile, the average number of colonies operated by the few remaining beekeepers has increased, but not enough to fully replace the diminished numbers. Many years ago, it was common for full-time farmers to handle no more than six colonies. A big commercial beekeeper might have 800 hives. In the 1950s, only two or three outfits in the world operated 10,000 hives (I can think of Mexico's Miel Carlota and America's Jim Powers and perhaps the Miller family.) When I immigrated to Canada (around 1975), the biggest Canadian bee holding (3,000 hives) was controlled by Homer Park who hauled packages up to the Peace River country from California. Today, there are a dozen Canadian beekeepers with at least 5,000 hives each. Not far from my home, there are two beekeepers with over 10,000 colonies each. My province of Alberta has seen a huge consolidation in beekeeping. In 1950, Alberta's 4200 beekeepers held an average of 12 hives each. Today, there are only 800 beekeepers, but each operates an average of 353 hives. By the way, with 282,000 colonies of bees, Alberta now has about 50,000 more colonies than the province had when Colony Collapse Disorder was first in the news ten years ago. Economics has increased colony count here while decreasing it in places like Oklahoma.

Time to get back to Time magazine. I am aware that winter losses for most North American beekeepers are higher than keepers can afford. It used to be expected that 15% of colonies would die each winter, according to statements made in the 1970s by commercial beekeeper and research scientist Dr Don Peer. Losses of 30% are frightening. Especially when that is an average. It means some beekeepers lost a whole lot more. For some operators, there is no recovery. Since those 30% averages have been sustained in most parts of the USA, research is conducted to try to find the cause. Everything from varroa mites to neonicotinoids to genetic weaknesses have been implicated.

A few last words. I am always troubled when anyone oversells their product. In this case, Time magazine's feature article is the product. On their website, you can link to a video they title: "Why Bees are Going Extinct" - honey bees are NOT going extinct. But perhaps beekeepers are. While the USA hive count fell from 8 million colonies in 1920 to 4 million in 1970, the number of people owning bees fell from 1.2 million to less than 100,000 in the USA today. A ninety percent drop. While it is true there are fewer hives in industrialized countries, the developing world has more honey bees today than it did 50 years ago. Vietnam, as one example, has gone from 7,000 colonies in 1996 to over a million today. Rather than going extinct, some researchers point out that the number of bee colonies worldwide is up considerably - in fact, according to Aizen and Harder, authors of an extensive study, managed bee hives increased 45% since 1961 globally.

I want to add that Time's articles about the honey bees (sans the alarmist headlines) are mostly very accurate and well-written. The main author Bryan Walsh has done a very good job. I appreciate that even though he used Einstein's image to attract readers, and he repeated the apocryphal Einstein quote, "If bees go extinct, humans will be dead in 4 years," Walsh says Einstein probably never said this and the statement is not true, anyway. Humans can survive without bees. Not as nicely, but we could survive. The Time magazine article points out that with fewer honey bees pollinating crops, food prices may rise and food varieties may dwindle. It is great to see bees being noticed by such a high-profile publisher. But it is a complicated issue. With changes in agriculture (chemicals, of course, but consolidation, too), climate, and pollination habits (monoculture is not good for bees), the bee losses can not be explained simply. No wonder it has been a difficult puzzle for bee researchers to solve.

Another movie about honey bee deaths? Why not? It appears the public isn't tired of hearing about dead bees yet. The latest installment is "More than Honey" which was filmed on location inside a beehive studio somewhere in Switzerland. Last year it was the BBC's "Who Killed the Honey Bee?" a great flick with lots of words and phrases like catastrophe, frightened, incredible death rate, disaster... you get the picture. Other recent honey bee films have been Australia's "Honey Bee Blues", "Vanishing of the Bees" (narrated by Ellen Page), "To Bee or Not to Bee" (a David Suzuki documentary), "Queen of the Sun", "Silence of the Bees", "Dance of the Honey Bees" (from Bill Moyers), "The Strange Disappearance of the Bees", and Emmy Awarded "The Last Beekeeper" - just to name a few of the best known. Too many? Probably - we risk desensitizing the public to the sting of bee disappearance. But it sure beats movies about Killer Bees like "The Swarm" from the 70s.

|

My home town has been hit by a flood. We would call it the "once in a century flood" but we had that back in 2005. We are told, however, that this flood beat all records for high-water levels over the past 90 years. Calgary has a bit over a million folks living here. 100,000 people were evacuated from 25 neighbourhoods. The hundred or so skyscrapers in the downtown had their basement parklots filled with water - some of those big buildings had four feet of water in their lobbies. The zoo is built on an island that submerged. First time that's happened in living memory. The animals survived, but the hippos were lifted by the swollen river and swam up out of their enclosures. We thought they were headed downstream for Saskatchewan, but they were caught before they were swept away. If you'd like to gawk at some astonishing pictures, here's a good link.

I have heard almost nothing about the city's beehives. The Calgary Bee Club sent out bulletins offering help with trucks and trailers to relocate unlucky hives, but it seems people here have very few (if any) kept colonies down by the riverside. South of town and out on the prairie, there were likely a few yards hit by the high water. Beekeepers will need to sterilize equipment flooded by city water. It wouldn't be smart to skip that chore. (By the way, the photo above is one of my yards during an earlier flood, along the Frenchman River in Saskatchewan. Look closely, you won't see the hippos.)

A half hour south of Calgary is a town aptly named High River. A week after the flood, High River still had 13,000 people homeless. There is one large bee outfit in High River, the Greidanus family. They lost at least 300 hives, washed away in the river, and they reportedly had close to a foot of water on their honey house floor. According to the farm paper, the Western Producer, their extracting equipment wasn't ruined, but they have layers of silt and mud on the shop floor. The biggest loss will be the hundreds of hives and the lost honey crop.

What caused the worst flood in Calgary's history? A storm slid up from Colorado, then became trapped in the foothills of the Rockies just to the west. There were 14 inches of rain in a bit over a day. That deluge, plus glacial melt and runoff from snow, overloaded the Elbow and Bow Rivers which meet in the city's downtown. The rest, as they say, is misery.

I presented beekeeping to my daughter's Grade 1 class today. It worked really well. I have two kids at the same elementary school, the older already in Grade 5. So he helped carry in the materials we used, and both he and his little sister were a big part of our hour-long discussion of bees and beekeeping with the little people. If you've forgotten, first graders are about 6 years old in the North American system. I was really encouraged by the enthusiasm the class has for nature in general, and bees in particular.

If you have had to talk about bees to any group, then you know the biggest problem is trying to figure out what not to say. Most of us could talk for hours. Pollination, honey, beeswax, queen bees, bee stings, bee hives, bee yards, flowers, sunshine, drones, workers, swarming. And then the kids want to know if bees sleep or if they talk, and you've got another two hours of material. The biggest challenge when talking about bees is deciding what to leave out.

|

We began when my 6 and 11-year-old assistants entered the class room clad in veils and white suits. One carried an (unlit) smoker, the other a big black garbage bag which was handed to me. "Want to see a bee?" I asked, shaking the big bag. The audience wasn't too sure. I didn't let them wait long. I opened the bag and pulled Benny the Bee out. He's our big stuffed mascot. You've seen him up at the top of this web page. A stuffed bee is an excellent model for children - we talked about insects, numbers of legs, body segments, and eyes and realized that Benny the Bee is not really a bee. The prop helps kids remember 6 legs and 3 segments, though. Then we realized that Benny has no stinger, which makes him a drone. That leads to some family history (What? 50,000 sisters?? Yuck!), and introduces the queen, though we steered clear of discussing haploids and parthenogenesis. After ten minutes, we used the Smartboard for a bit to show real bees, leading up to nectar collection. By then, even the most enthralled post-toddler is waning, so everyone stood up to do a bee waggle-tail dance. It is enough for kids this age to dance quickly if the flowers are close, and turn around and dance slowly if the flowers are far from the hive and in the opposite direction as the sun. Beyond that, you are just meddling with developing minds. After standing, stretching and dancing, the children are refreshed and ready for another ten minutes of bee talk. We ended by handing out little 4 x 4 (inch) pieces of brand new wireless foundation. The kids love the take home gift, it isn't messy and sticky, it smells like wax, and it has the great hexagonal pattern. Do it again next year? You bet!

|

I heard today, rather late, of the death of a young beekeeper. Jason Escapule was only 39. He lived south of us, down in Idaho, where he ran one of the largest round comb honey bee farms in North America. I was told his Harvard Yale Honey Bees farm, located in Princeton, Idaho, was turning out 50,000 combs of honey a year. Jason died in an accident - he was reportedly learning to fly an ultralight aircraft. It was a tiny plane with three wheels, and is sometimes called a trike-plane. Police say Jason was a student pilot, but his trainer, an experienced 58-year-old pilot, was with him when the little craft was seen spiraling downwards towards an open field. They both died on impact. That happened in November, about six months ago. Jason Escapule is survived by both his parents and several cousins. Our belated condolences to Jason Escapule's family and friends.

I had a phone call a few years ago from Jason when he was new at his honey business. We chatted about strategies for expanding his operation, which he was just acquiring. I suggested he not get too big if he wanted to stay a comb honey producer - it is extremely labour-intensive and the beekeeper has to stay on top the entire operation. So he had only a few hundred hives - not several thousand as some western farmers operate. He liked the idea that he could produce a hundred combs from each of 500 hives and market 50,000 packages of honey. That's about $300,000 in revenue. It takes a lot more bees to produce that much liquid honey, plus it takes big trucks and honey holding tanks. But comb honey making is a lot of work. My daughter Erika and her husband Justin produced 30,000 combs this year - so we know it's a lot of work.

I'm not sure what has happened to Jason's business. It is always hard to pass along a small operation of any sort when the spark plug is no longer there. But this young man was not even 40 and died unexpectedly, tragically.

What would it be like to keep bees for 80 years? You could ask 92-year-old George Birks, who started back in the 1920s. The price of a loaf of bread was 9 cents; a pound of sugar was 7 cents; gasoline was 30 cents a gallon. And honey retailed at about 5 cents per pound. You'd be happy earning a dollar or two a day. When George Birks began his 80-year beekeeping odyssey, he may have driven an open two-seater 9-horsepower Adamson.

George Birks was introduced to the sport of bee-dodging by his uncle. As a Brit, he would have experienced the bombs and sugar rationing of the Second World War, the demise of small farm holdings, and changes in climate. Mr Birks says he started more than 80 years ago. By the time he was 12, he was an experienced bee wrangler and became a founding member of the Hartlepool Boys High School Boy Scout group, where he earned his bee farming badge. By the way, if there is any doubt that he has been living in the English countryside, he was originally from Hartlepool, but now lives in Arkengarthdale, which is near Reeth, in Upper Swaledale, and he has chaired bee clubs in Yorkshire, Beverley, Cottingham, Alnwick, and Harrogate. This week, the Richmond and Beverley Beekeeping Associations presented to him a certificate commemorating his 80 years.

>A couple of weeks ago, a warehouse fire destroyed a bee outfit's shop at an old kibbutz in Israel. A dozen hives were lost, along with processing equipment and supers. The kibbutz was founded in 1934 by progressives from Poland and Croatia who planted orchards and made the desert blossom. The honey farm at Kibbutz Gat is mostly intended to help with pollination - Gat is home of Primor, one of Israel's largest juicer makers. The pictures of all the wrecked equipment on the fire fighter's website remind me of a honey house fire I once had. Or, rather, those photos show me what might have happened had not been able to control the blaze. I was lucky, I was able to smother my flaming wax melter. If you jump over to the website with the burnt hive photos, you can see how bad things could get. I don't know how many honey house fires happen each year, but I'm sure there are a few too many. A beekeeping colleague in Nipawin, Saskatchewan (Dr. Don Peer) years ago built a very long narrow honey shop: "Just in case of a fire," he told me.

|

Today is the 60th Anniversary of The Conquest of Everest. It was 1953, Queen Elizabeth was just about to begin her first day on the job as queen of the world's imperial empire. In 1953, a typical TV was a box bigger than the average 'fridge. And it took 3 days before the world knew whether Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had climbed the peak of the mighty mountain (named for a British Tea Company surveyor), or if they had died trying. As ABC news said today: "Sixty years ago, on May 29, 1953, a New Zealand beekeeper and a Nepali sherpa reached the peak of Mount Everest in Nepal."

Yes, Sir Edmund Hillary was a New Zealand beekeeper. Not the backyard, one hive under an apple tree sort of beekeeper, but a real-life honey farmer. And for a few seasons after his famous conquest, he went back to tending the 1,400 colonies scattered around his island home. At the time, he didn't think the climb was a big deal and he expected his moment of glory to fade quickly. It didn't.

Hillary climbed Everest in 1953. Off season, he continued exploring remote corners of the Earth - in 1959, he wrote a book about his discoveries in Antarctica. 1959 was also the last year he was a commercial beekeeper. Here, from his book A View from the Summit are Hillary's own words about his beekeeping experiences: "My brother Rex was a year younger than me and he, too, was part of our family beekeeping business. Rex and I worked well together as a team. He was smaller than me but very strong and vigorous. In the friendliest fashion we competed energetically with each other, often running side by side with heavy loads of honey to pile them on our truck...we actually enjoyed the beekeeping. Our thirty-five apiaries were spread out on fertile dairy farms up to forty miles away, so we were always on the move. The spring and summer, when the bees were gathering nectar, was a time of great excitement. The weather made beekeeping a tremendous gamble, of course. Each apiary we visited could have a substantial crop of honey in its hives or almost nothing. Rex and I reveled in the hard work."

|

Canada's spring has been frightfully slow this year. Snow was on the menu coast-to-coast-to-coast in April and early May. As seasoned beekeepers will admit, wintering bees at our latitude is not too hard until mid-March. In springtime, cold damp windy weather can take a heavy toll. Just when you feel you've done a great job packing and preparing the boxes, and losses don't seem significant, you find fewer live hives with each spring inspection. This is when queen losses become apparent and small populations don't achieve critical mass. Bees drift, the elderly succumb, the failing queens expire.

Things were not so bad in southern Alberta. Erika told me winter losses were around 15% down in Milo, Alberta. I haven't been out looking at those bees - they are now Erika and Justin's project to manage. But I have been listening to the results other beekeepers have posted, and it's generally not so good. My friend John Gibeau, owner and operator of the amazing Honeybee Centre out near the Pacific coast, has told the Surrey Leader that things have been better. Mostly due to high winter losses several years in a row, blueberry pollination is in trouble. "...there's not enough bees to go around," according to the news pieces "Bee shortage stings farmers, beekeepers." Mr Gibeau reported that new blueberry plantings, increased colony density on existing fields, and fewer commercial hives has meant "growers are out thousands of colonies." Growers need about 4 hives per acres to assure a good fruit set.

|

Here's a new twist on the old fashioned Honey Massage. This one actually uses old-fashioned honey. The sticky massage seems to be increasingly popular in Europe, judging by the YouTube videos from Romania, Czech Republic, and especially videos such as this news clip (Was ist eine Honigmassage?) from Germany. In fact, the German Honey Massage videos outnumbered all the others when I did a search.

So what's the point of a honey massage? According to numerous websites, honey is the only really natural massage ointment available. That is likely true. This series of 'how-to' videos will teach you how to do the massage and will tell you the purported health benefits: "It nourishes the skin, stimulates and moves lymph, frees up the fascia, and creates a space for stagnant fluid." And many more things. I am always leery of multiple and diverse health claims, and I don't understand what this instructor means by "moving lymph," "freeing fascia," and especially "creating spaces for stagnant fluids" - though I'm not really keen on hearing a definition for the last one. However, the video will teach you how to prepare and perform the honey massage.

We are always happy to see new uses for old honey. And I suspect it really does work magic on sore tired muscles. Certainly it helps beekeepers sell more honey. So, of course the honey massage is a great idea!

Enjoying spring?. Soon you may have even more of a good thing. According to a detailed study published by a group of geophysicists associated with the American Geophysical Union, spring will start arriving 17 days earlier in the north, if we think of spring as the time flowering trees burst into blossom. Just so you are clear on this - spring will remain March 20 or 21 in the northern hemisphere (unless the Earth rolls over on its side); spring will continue to be the day that nights are 12 hours long, and then begin to shorten as we approach summer. But some smart geophysicists used their high power computers to model Future Earth, looking ahead to 2100 and found that climate changes already occurring will force tulip poplar and linden (basswood) as well as sourwood and acacia (black locust) to flower weeks early.

Alongside articles about dipolar magnetism and low-frequency seismic waves, the journal Geophysical Research Letters cites a simulation credited to four authors who projected budburst of deciduous North American trees, finding several troubling results. With a warmer climate, trees will blossom earlier (you don't need your Princeton PhD to understand that). But according to the research, the various trees that once bloomed over a couple of months will cluster closer together, resulting in what the paper's abstract euphemistically calls "the potential for secondary impacts at the ecosystem level." This means your bees, of course. Instead of a long minor honey flow, they may have a more intense, short and sweet nectar rush. The change will happen over a few decades, so your management skills will have time to adapt. The other summary point the research makes: "We expect that these climate-driven changes in phenology will have large effects on the carbon budget of U.S. forests and these controls should be included in dynamic global vegetation models," Ominously implying that the rate of climate change will accelerate, the so-called "Snowball Effect," or, in this case, the "No Snowball Effect."

|

Charles Darwin was a famous geologist before he published his revolutionary evolutionary treatise. He was also a well-rounded naturalist. It was Charles Darwin who discovered that some bumblebee species gnaw into the side of deep-throated flowers, cheating their pollination obligation. These are short-tongued bees. Their excuse is that they can't reach the nectar, so they steal. The consequence is the flower loses its nectar without the benefit of pollination. (There are other bees, long-tongued sorts, who later correct the damage, so the flower can reseed.) Flowers have been trading food for pollination services with the animal kingdom for at least 100 million years. Darwin realized that the robber bee's activity was not within the usual evolutionary scheme. Although the flower may have evolved deeper and deeper tubes while a compatible bee evolved a longer and longer tongue, neither expected an interloper to wonder onto the scene, perhaps blown in by a windstorm many generations earlier. With enough time, the flower may develop a toxic base to discourage theft. When Darwin discovered this bad bee habit - and wrote about it in a naturalist journal - he recognized, correctly, that the bee's behaviour was learned, not inherited.

Recently, a bumblebee expert, David Goulson, added to Darwin's discovery. Goulson, at Britain's University of Sussex, spent a couple of summers with his assistants in Switzerland. There they tracked bumblebees amid alpine flowers called yellow rattle, which hides its nectar deeply. Their observations took them to 13 different mountain meadows where they spotted the bumblebees and discreetly followed them, like undercover cops witnessing crimes. After each bee was seen robbing 20 flowers, a profile was written up and filed. As it turned out, novice bumblebees watch experienced burglars - and learn their techniques. They inferred this from the fact that most bees in the meadow poke holes into the same side of the yellow flower's base, either right or left; not both, and not randomly. If you look at the picture, above, you can see that the flowers are rather tight to the stem. From an observer's vantage, the right side is obvious. Although there is no advantage in selecting the right (or the left) for drilling, biting, and poking through to reach the nectar, the bumblebees tend to always work the same side as other bees are working. And it may change the following year, when everyone pokes left, for example. And it can vary from meadow to meadow. The point is, some original thief makes a choice each year, sticks with it, and everyone else copies. Learned behaviour at its finest.

|

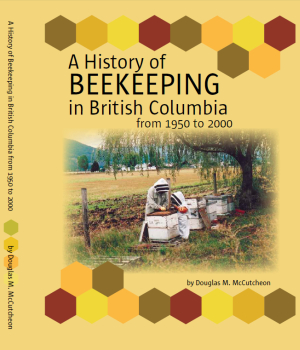

I have found some time to read the book, A History of Beekeeping in British Columbia from 1950 to 2000, and have thoroughly enjoyed it. Like most prairie dwellers, I have trekked out through beautiful British Columbia as often as possible. So I am somewhat familiar with the areas the book delves into - places with the names Central Cariboo, Skeena Valley, East Kootenays, and Maple Ridge, among many others. These names always conjure great memories of gorgeous scenes and wonderful places. But I lingered longest among the dozen pages devoted to the Peace River Area. When I was but a teenager, I drove up to the Peace, thinking I should become a beekeeper there. The scenery is wonderful. The Peace River, a part of the Arctic-bound Mackenzie watershed, is dramatic and inspiring. But, of course, it was the rumours of 300 pound honey crops grown from packages of bees that really enticed me. As it turned out, an opportunity opened up for me in Saskatchewan, instead. But I've often wondered how my life might have evolved had I gone to work for Ernie Fuhr, or the Van Hans, or someone else up on the Earth's rooftop, and then slowly began building my bee farm somewhere just off the Alaska Highway. When I read the BC Bee History and the clips about 430 pound averages, well it seems whimsical now. I'm glad that the author, Douglas McCutcheon, has collected the stories of the bees and beekeepers that belong to these places.

Part of the great beauty of British Columbia, and the great challenge in preparing a book like this, is centered on the extreme diversity of climates, agricultural regions, and environmental domains of the province. The author does a nice job of pulling it all together. From rocky-peaked mountains to foggy islands, bucolic pastures to rolling plains, BC hosts beekeepers everywhere, all with unique conditions, many with unusual forage crops, some engaged in a climate with Mediterranean bliss, others struggling in a severe continental environment. It all makes for an interesting compilation.

There is a lot to enjoy in the History of Beekeeping in BC. We tend to ignore our history too readily. And that condemns us to make blunders that might have been avoided. But the real joy in a book like this one comes from reading the dozens of sketches about the characters who were beekeepers last century. What would beekeeping be without "characters" anyway? Who would dare keep bees, if not the folks who live a tad bit differently from the rest of society? We are indebted to Doug McCutcheon and the editors and assistants at the BC Honey Producers Association who worked so hard to capture the memories, organize the stories, and publish the book. To them, many thanks.