Welcome to The Bad Beekeeper's Blog

2008 Blog 2009 Blog 2010 Blog 2011 Blog 2012 Blog 2013 Blog 2014 2015 Blog

A Quick Buzz Back through 2014

With another year behind us, we look back at some of our favourite stories from 2014.

Jan 25, 2014 |

Scientists discover: Honey bees that drink wine live longer. |

Feb 9, 2014 |

Researchers outfit 5,000 bees with RFID tags and watch them pollinate apples. |

Mar 23, 2014 |

The National Farmers Union came out with a strong environmental position, "Corporate profits trumping ecological needs." |

Apr 14, 2014 |

Beekeepers claim a quarter of bees died while pollinating California's almonds from a toxic mix of poisons used on the trees. |

Apr 27, 2014 |

The rise of honey prices and cost of bees has led to a rise in bee thefts. |

May 25, 2014 |

My posting about an anti-GMO march in Toronto that included a funeral for bees resulted in hate mail sent to this blog. I must be doing something right! |

June 5, 2014 |

Our annual participation in the ALS walk/run/wheelchair roll. Later in the year we took the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge, too. |

June 12, 2014 |

A look at the environmental impact of spreading an invasive insect species - the honey bee. |

June 26, 2014 |

Glow-in-the-dark bees are invented by scientists who genetically modify the humble honey bee. |

July 9, 2014 |

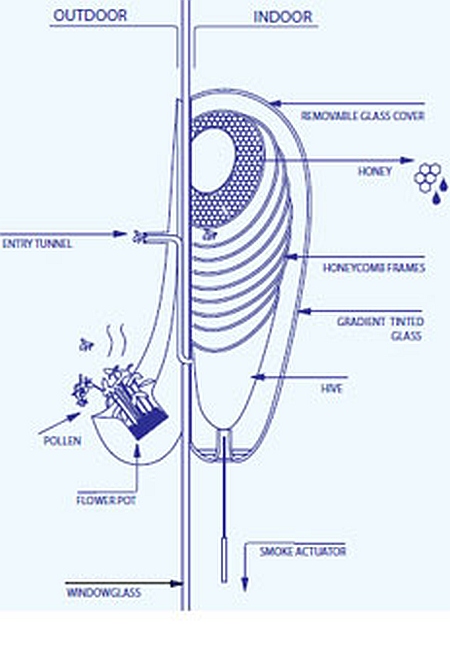

An indoor beehive is designed by Philips, the super-huge Dutch medical and household manufacturing company. What could possibly go wrong? |

July 17, 2014 |

"Our Bees, Ourselves" is the name of a New York Times Op-ed piece written by UBC's Mark Winston. We talk about it so you don't miss the story. |

July 23, 2014 |

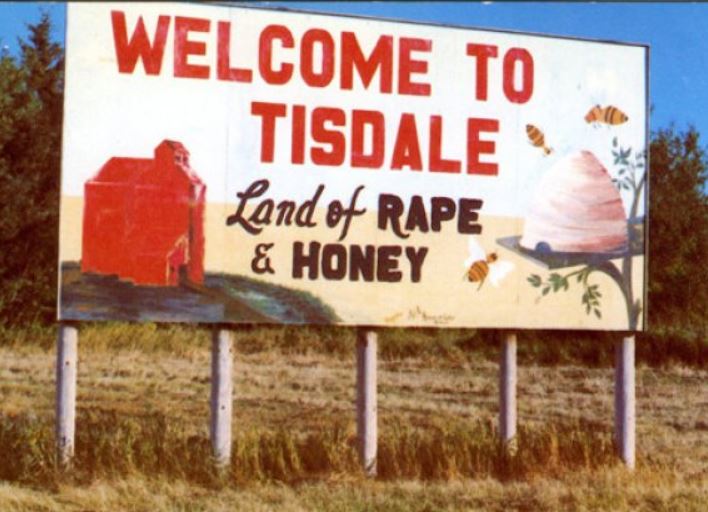

We look at how canola was invented by agriculture scientists. |

July 27, 2014 |

The Canadian Prime Minister's wife saves a crowd from bee stings by putting the lid back on a mean hive of bees. Laureen Harper - Cool in the line of fire. |

Aug 2, 2014 |

Actor Morgan Freeman takes up beekeeping in a big way on his Mississippi farm. |

Aug 24, 2014 |

Robotic bees are being built to replace honey bees for pollination. |

Sep 4, 2014 |

"See You in Court," says Ontario beekeepers who sue Bayer for $450 million. |

Sep 9, 2014 |

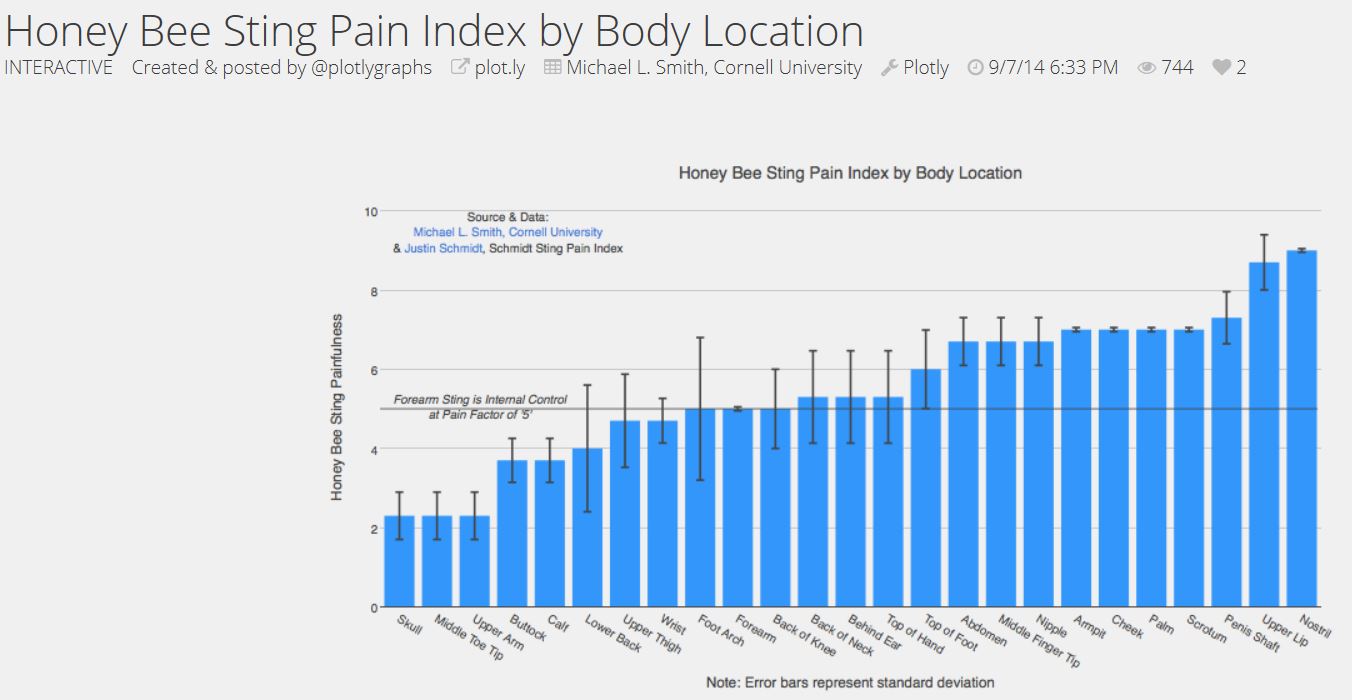

A scientific study of the worst body part to get stung on. It's not where you are thinking. |

Sep 19, 2014 |

Someone is poisoning honey bees in Manitoba by dumping poison on or in hives. Who could it be? |

Oct 9, 2014 |

Newspapers around the world claimed that 800,000 bees attacked and killed people in Arizona. But the story wasn't quite true. |

Oct 18, 2014 |

Honey prices, adjusted for inflation, have never been higher. Congratulations, beekeepers, for finally getting paid for your work! |

Nov 8, 2014 |

In A New Origin for Bees? Maybe bees did not originate in Africa, contrary to what we used to think. |

Nov 22, 2014 |

Is climate change putting bees and flowers "out of sync" with their mutual pollination needs? |

Nov 24, 2014 |

What does it take to pack 50,000 combs of honey? |

Dec 2, 2014 |

Hive beetles arrive in Europe - yuck! |

Dec 8, 2014 |

Radioactive sterile Medflies are sent to Croatia to save fruit crops (and maybe bees). |

Dec 10, 2014 |

An elephant charity uses honey bees to save villagers and elephants. |

Dec 29, 2014 |

A "Honey Bee Sauna" looks at using heat to kill varroa mites. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A German "crowd sourcing" fund wanted 10,000 Euros to build honey bee saunas. Within a few weeks, they had over 60,000 Euros in pledges - that's about $75,000. I guess that the contributors don't realize bees can die in a sauna. Back to that in a minute.

Varroa mites kill bees. To eat, the nasty mite-creatures grab hold of bees and suck up their insides. Eventually, all colonies with booming varroa mite infestations die. That's why beekeepers try to poison varroa mites - usually treating their bees with pesticides. Pesticides can leave trace chemicals inside the hive and become dangerous to bees and bee handlers. The mites may evolve resistance against the poisons. Presently, various chemical treatments seem to be the only effective and widespread weapon against the deadly varroa mites. But other methods are being tested.

Just as mites evolve to resist chemicals, honey bees may evolve to resist mites. This is the idea behind the celebrated Russian bee. Honey bees found in eastern Russia seemed to have evolved to live with mites. The claim is that most untreated honey bees will die, but a small subset will have some genetic quirk that will allow them to survive varroa attacks.

Genetically quirked bees will reproduce and repopulate the ecological niche lost by their vanquished sisters. This may have happened in isolated areas, such as Siberia. Unfortunately, when the Russian bee was brought to North America, its genetic advantage was quickly diluted by other honey bees already extant in the hives of commercial beekeepers. You see, queen and drone bees fly many kilometres to clandestine rendezvous hangouts where they indiscriminately mate. This evolved habit prevents honey bees from becoming inbred and fosters genetic diversity - within the same colony any two randomly selected co-working workers are likely to be half-sisters, not full sisters. Although this diversity gives many advantages to a colony, it almost kills the idea of maintaining pure-bred naturally mated lines of pest-resistant bees. It takes a good queen breeding program to maintain stock that keeps a line of honey bees imbued with hygienic behaviours and other strategies that suppress varroa populations. There are such queen breeders around and it can be done - but you can see that without discipline and diligence, varroa will creep back into an operation.

So, if chemical treatments eventually fail and genetic solutions are hard to maintain, what might be done to fight the dreaded varroa mites? Some beekeepers have lured mites to drone brood, then discarded the comb; others have reported some success dusting powdered (icing) sugar on bees to extricate mites. Greasy vegetable oil sprayed on the bees may slow down mite infestations. A completely different idea - heat - has been occasionally promoted and seems to be going through a bit of a popularity surge. Varroa mites, it seems, can't cling to honey bees if the temperature is hot. This has led to a number of schemes that warm the inside of a hive (or a cage of bees) until the mites fall off. Unfortunately, this does not kill the varroa mites, it just dislodges them - chances of success are likely pretty sketchy using this system.

The USDA studied this idea 15 years ago. You can read their report at this link. Here's the problem: at temperatures of 40ºC (104ºF) and higher, mites slowly fall off honey bees but bees begin to suffer heat stress. Honey bees, as you likely know, try to keep their nest temperature at about 35ºC (95ºF). Way back in 1791, Francis Huber discovered that even on the hottest summer days, bees did not allow their nest to rise above 99ºF. Remember, mites fall off at 104ºF. So it is hard to get a high enough temperature inside a hive to dislodge varroa mites. The bees will fan and evaporate water and reduce the hive temperature so they do not die of heat exhaustion and so their wax home doesn't melt into a candle-like blob. High air temperatures dislodge mites if the temperature is warm enough for a long enough period of time. Higher temperatures (over 45ºC or 113ºF) will make the mites fall in just a few minutes, but will also kill honey bees more quickly. The USDA study shows that bees get crispy if they are exposed to too much heat - or even a little heat for too long a time. Quoting the USDA 2001 study: "Overall, heat treatment is a risky procedure. Even 40ºC, the lowest temperature that can remove all the mites is perilously close to temperatures that kill bees."

With these potential problems in mind, I was surprised to see that a German Crowd Sourcing Fund was able to quickly raise a huge amount of money to build a Bee Hive Sauna. The crowd sourcing goal was 10,000 Euros. They have over 60,000 Euros in pledges - that's about $75,000. Their self-promotion site includes the non-Einstein quote ("...if all the bees die, in 4 years you will too...") and it includes lots of Wir retten Bienen ("We save Bees") subtexts. So, the promoters know how to appeal to the heart-strings of the misinformed. My guess is that the contributors/donators/funders don't realize that bees can die in a sauna. The trick that keeps the bees alive, according to the inventor, is that (with his Bienen Sauna) "The Bees do not roar." (OK, maybe it's the Google Translator. The original German is Die Bienen brausen nicht.) I have never heard of roaring bees, but roaring seems like a problem to be solved. I will probably get the story wrong, so let's allow the inventor, Engineer Richard Rossa, to explain:

"The bees do not roar"

"In my trials I came to the realization that roar of bees is not caused by a slow

heating of the ambient temperature, but by increased CO2 content of the air. However,

this effect does not occur in the treatment with the bees sauna. If necessary, fresh

air is supplied at any time. This is done controlled so that no draft is produced.

"Holding the air temperature constant between 40°C and 42°C, all Varroa mites,

which are long enough exposed to this temperature, irreversibly damaged. Should any

of Varroa mites survive, they are so damaged that they can no longer reproduce.

Broodless colonies are treated for 45 to 60 minutes. Those with brood take two hours

because it takes longer to warm through the brood cells. Then the device switches off

automatically. In the entire time temperature and humidity are constantly monitored

and regulated in the hive."

It appears that by ridding CO2 from the hive, the bees won't roar. If you read their website, you will see that (for about $1,000 per unit) it will be just the varroa mites that do the roaring. Rossa says that the temperature inside the hive/sauna will be kept at 40 to 42ºC. As we have already seen, this is a good bit warmer than the bees like, so I suspect some energy will be wasted by the bees as they gather water and circulate air to get the hive temperature down to their preferred 35ºC. Or I could be wrong. It could be that I am just an old-fashioned cynic who is spouting off about any product that has been tried in a number of commercially available guises over the past few years (see the Mite Zapper and the Varroa Controller.

Maybe I am cynical because some gullible people will quickly fund any cool yuppish idea - even if the procedure has been shown problematic by USDA researchers. However, I do not have a PhD in "Co-operative Communication Strategies for Politics and Media", whereas Richard Rossa's partner, Dr Florian Deising does. He was "a management consultant, financial manager [who] led international projects in large corporations... [But 2 years ago, he] got out to make as it were full time our world a better place". I suppose these guys have their heart in the right place and they obviously know how to work a crowd for money. And perhaps they know how to keep bees from roaring in the sauna. It would be great if some sort of well-engineered hot-hive can actually kill varroa mites without hurting bees. That would eliminate chemical treatments. But at almost $1,000 for each device, the Bee Sauna will probably meet limited success. Personally, I think the long-term future for varroa control will be in genetic manipulation, not in heat. But check out the Bee Sauna at wir-retten-bienen.org ("WE SAVE BEES.ORG") for yourself and make your own decision.

|

|

15 Amazing Incredible Uses for Honey!

I came across a list. It's one of those "7 Amazing Habits of the World's Most Successful Dogs" sort of lists. But this one is about honey and the title wasn't written as run-of-the-mill click bait (such as today's headline on my blog), but it is more subtle: "15 Household Uses For Honey".

Fall is honey-using season. But now the autumn holidays (Rosh Hashanah, Thanksgiving, Halloween) and the final honey harvests are behind us. We realize that honey sells better and disappears from pantries more quickly in the fall. Winter is just days away. Still, beekeepers can initiate a few extra sales during the upcoming cold and flu season. To that end, the Mother Earth Living's piece ("15 Household Uses For Honey") deserves a visit.

I am not going to list all '15 household uses' for honey. Several on the list are redundant. Burn Balm and First Aid, for example, both encourage spreading honey on ailing body parts as an antiseptic and as a healing home remedy. Home remedies, in fact, make up 8 of the 15 Household Uses for Honey - including treatments to fight drunken hangovers, sore throats, nervous tummies, stubborn coughs, and persistent pimples. Somehow, I doubt revelers will be looking for honey on January 1st, but it's worth mentioning.

Of the fifteen honey uses (you can think of more) only two are appetizing (drizzle on cheese; dab on fruit), one recommends honey as an energy food ("Workout Booster"), and four are beauty-bath and handsome-hair regimes. This breaks down honey's advantages to culinary, medicinal, energizing, and beautifying. Not a bad bunch of attributes. (In a very old bee journal I saw a whole new category - automotive maintenance... it seems a Model T radiator will not freeze up in winter if a judicious amount of honey is mixed in with the water.)

I am of a mixed-mind when it comes to making these sorts of honey-use recommendations. I think a beekeeper can appear rather flaky if he/she pulls out a long list of miracles that honey performs. I do think that most of the list is valid and accurate - anecdotally, I have witnessed honey healing nasty burns and settling anxious stomaches - but as a consumer, I am always leery when any food or supplement is touted as all-inclusive. It suggests that either some exaggeration or some desperation is going on. However, I think it is useful for the salesperson-beekeeper to know these uses and be able to respond to each in an informed way. Any valid application that encourage honey consumption (and is beneficial to the customer) is worth knowing about - even if it is best not heralded as part of a sales pitch.

|

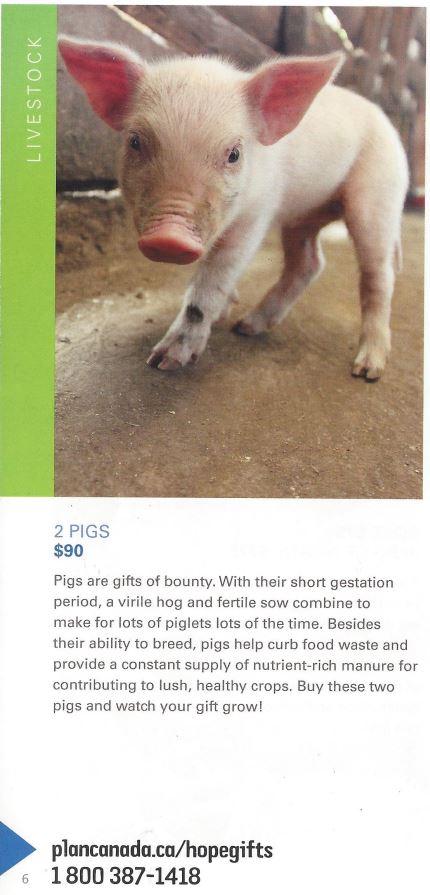

Our Pig

We bought a pig. We will keep it in Africa. It wouldn't be fair to make our pig live in our house in the city. So Wilbur will be staying with a family in Africa.

As I am sure you have figured out, our family made a contribution to a charity. Our kids (ages 12 and 8) broke open their piggy banks and we all put a few dollars towards this ungulate project. $90 buys a (married?) couple which goes to a family that will benefit from the boars.

The charity that will provide the porkers is Plan Canada. It has been around for about 80 years. Other Plan Canada projects include the anti-malaria Spread the Net program, Because I Am Girl, and a variety of community programs. The thing I like about this outfit is that they try to break the cycle of poverty by providing tools to families. Those tools may include a couple of pigs which (in theory) are not to be eaten but rather will be used to raise more pigs, some of which may be sold or, well, maybe cooked. But you get the idea. You can donate money for sheep, goats, chickens, or seeds, shovels, and hoes. These are intended to enhance economic security, but Plan Canada also provides wells for clean water, builds schools, and makes sanitation systems for villages. The group also sponsors women and girls' education in a big way.

In past years, Plan Canada would also provide beehives if that's where you wanted your money to go. Their blurb mentioned pollination, "saving the bees", honey, wax, and self-sufficiency - but their accompanying photograph was of a modern, white, two-storey Langstroth hive. I had trouble with the idea and didn't donate to it. I thought Plan Canada should find a way to help local beekeeping by offering local equipment. Our western hive-style might work in some places, but maintenance of such equipment would be a hassle in many parts of the world. Plan Canada seem to have agreed.

Anyway, if you would like to help, Plan Canada seems a worthy outfit. If you live in the USA or elsewhere, I think Plan Canada is part of Plan International so you could contact them. If you are not keen on farm animals and clean water, there are other groups that provide famine and emergency relief for the truly desperate. It seems Plan Canada is trying to use donations responsibly with the goal of helping families become self-sufficient. And who wouldn't love to buy a pig - and keep it at someone else's house?

|

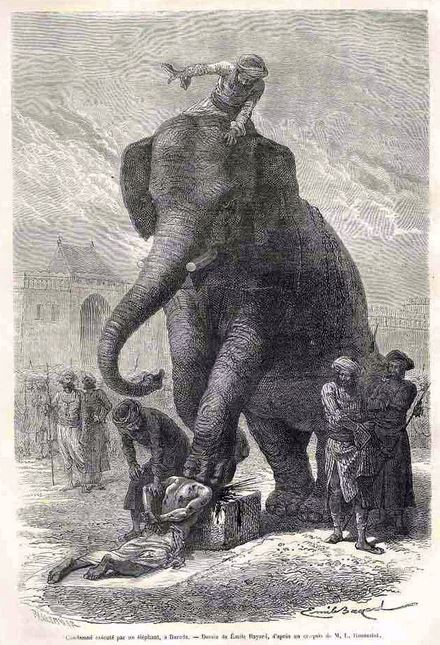

Beehives vs Drunken Elephants

Drunken elephants have been a problem for as long as I can remember. Elephants are known to booze-up, get rowdy, and attack farmers - sometimes even entire villages. A herd of elephants got drunk on rice beer in Assam, India, and then looted and destroyed a nearby community. Reportedly, they were mostly young elephants and were just looking for more beer. But unfortunately, four people were killed in the ensuing skirmish. Worldwide, over 100 people are killed each year by irritated elephants. The worrisome fact is that not all the elephants are drunken beasts during their murderous escapades - many of the killers are stone-cold sober.

Some environmentalists are (at least partially) excusing the elephants' riotous behaviour, suggesting it is in retaliation for human activity which continually encroaches upon elephant land. I think the environmentalists have a point. But no species has the right to take the law into their own hands - and revenge is a slippery, retaliatory slope which can only lead to an escalation of the Hatfield and McCoy sort. However, if the elephants are fed up with us, they certainly have their reasons.

Goons have been poaching and slaughtering elephants for generations, turning elephant legs into drums and flower pots and tusks into trinkets. Elephants are migratory mammals, traveling long distances as they follow seasonal changes for healthy dietary variations and for meet ups at watering holes and salty mineral springs. There they may share stories or even fall in love. But we have taken most of their rangeland for our own growing population, turning their trails into our roads and their meadows into our fields. The forest elephant in the Republic of Central Africa lost 60% of its population to poaching - the ivory is sold to fund human wars and, in other parts of Africa, terrorism. Elsewhere, humans in Laos, Sri Lanka, India, and 37 African nations have expanded cropland to prevent their own starvation. In the process, elephant numbers have plunged in the past few decades - the African elephant population, for example, has fallen from 4 million (1930) to 300,000 today.

For centuries, people have used elephants for work, warfare, and entertainment. As you can see in the pictures below, elephants have been employed in temples as living totems of Ganesha and executioners in India (the second image below is fuzzy, but it is an 1868 sketch of an elephant being forced to kill the man whose head is on the block). Elephants have given us circus entertainment in North America (as in Dumbo and Jumbo among thousands of others) and they have worked as draft animals throughout southeast Asia and general labourers in Europe (the last photograph below was shot by a US service man in Hamburg in 1945 - the elephant is cleaning up WWII debris after Allied bombing).

|

|

|

|

|

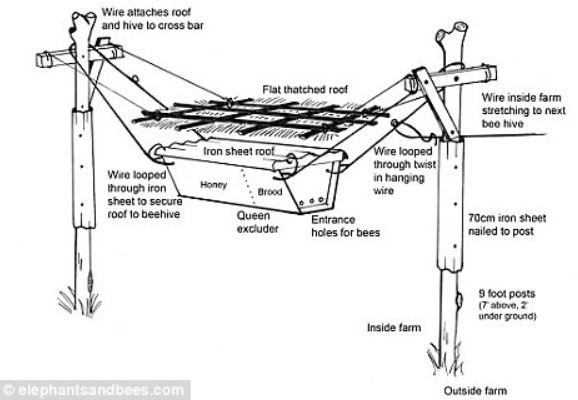

We have been abusive. But human women, children, and farm peasants pay the price when marauding elephants trample conventional fences and destroy crops. Elephants have learned to lift latches on gates and they have sought weak spots in wire and wooden fences when gates are locked. Subsistence farmers are sometimes ruined when elephants trash fields. But the pachyderms recognize beehives and steer clear of potential stings. So, a very bright Oxford scientist, Dr Lucy King, came up with a potential solution. It is based on the fact that elephants are afraid of bees.

|

For inventing a fence of beehives that reduces clashes between humans and elephants, the United Nations presented Dr King with the prestigious Conservation of Migratory Species award. She received the recognition because her fence is innovative, uses local resources, provides farmers with honey and wax, and because it actually works. First tested in 2008, it has stopped 84 out of 90 attempted raids in three different regions. It seems to fit culturally - three different African tribes have adopted the system. Beekeepers reading this will also recognize that the hive is elevated on posts and suspended by wires. This prevents nasty brood-eating mammals (as well as ants) from accessing the bee colonies. African bees typically nest in trees so these hanging hives are accepted by the bees - I suspect unoccupied boxes would attract swarms. (Since the elephants have learned to recognize the units as hives, dummy hives can be hung among populated hives - these are equally effective at barring the elephants.) Beekeepers will also recognize the construction shown here is a TBH (Top Bar Hive), which uses local materials, but Langstroth hives (as nucs) can also be used.

I think this is a brilliant idea. It satisfies the defensive needs of the local people without killing the endangered migratory elephants (they simply skirt the bees and the crops and continue ambling along their way). Dr King has placed a manual (which she wrote) on the internet so other groups may adopt her idea. Meanwhile, testing, refinement, and distribution of the beehive fence continues. You can - and should - visit elephantsandbees.com to learn more. You may also contribute to this effort by going to the Elephants and Bees donor page or through the UK's Save the Elephants charity. We are told that "100% of funds will go towards project-running expenses."

|

|

Sterile Radioactive Bugs Arrive in Croatia

Why did a kibbutz in Israel ship 380 million sterile, radioactive fruit flies to Croatia? That might be the most unusual introduction this blog has ever used. Here's the backstory...

Ceratitis capitata - the lovely but insidious Mediterranean Fruit Fly - is indigenous to the fruit belt surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. This includes Croatia. Normally, the Medfly does not wander far, so it spreads slowly. Unless it's boxed up in a crate of tangerines. Or figs, apples, peaches, blueberries, pomegranates, grapefruit, or some other wormy but nutritious carton of fruit. That's how the Medfly reached the States, New Zealand, Chile, and (I think) Australia. In Chile, New Zealand, California, Texas, and Florida, the bug was successfully eradicated. Hawaii is still fighting it. If you don't like worms in your oranges, it needs fought. The bug's life cycle prompts it to poke holes into ripening fruit and deposit eggs under the fruit's skin. The eggs hatch and the larvae (worms) eat, grow, and pupate. Even those of us who are free-range omnivores find the results a bit disgusting.

|

The Medfly can be sprayed into oblivion. That's how California eventually ridden itself of the scourge. Back in 1989, Governor Jerry Brown resisted aerial spraying on environmental principles. He authorized a ground assault, but the Medfly moved ahead of the program. Reluctantly (and almost too late), Brown agreed on blanket sprays which finally destroyed the fruit flies. (By the way, Brown is again governor. He is 76 years old now. He took over a bitterly divided, bankrupt state (only partly due to Arnold the ex-terminator, who was formerly in charge). California, under Brown, has recovered remarkably. There is finally a government surplus - The Economist says Brown is "so tight-fisted he is not above eating off other people's plates." Potentially a bit disgusting, but I digress.) In the end, helicopters sprayed malathion at night while the California National Guard inspected vehicles fleeing infested areas. Later, entomologists released sterile Medflies to seduce any holdout Ceratitis capitata.

This brings us back to Croatia and the friendly kibbutz. In 1934, Jewish settlers from Germany began the Sde Eliyahu religious colony. They built their stockade and tower settlement near the Sea of Galilee at 200 metres (660 feet) below sea level where malaria swamps and summer heat affected the early settlers and their precarious crops. They persevered, transforming their worthless tract of land into an agricultural oasis. Today the kibbutz and its 750 residents are entirely dependent on farm-related activities. Here is what Sde Eliyahu says about itself: "Many of our field crops and fruit are special in that they are cultivated according to the principles of organic agriculture. We were real pioneers in this sphere in Israel fighting for the exclusion of toxic fertilizers and sprays. To replace the latter, natural enemies of pests have to be found and activated." Pursuing natural solutions led to the establishment of BioBee, which is mainly involved in bumblebee pollination within greenhouses, and Bio-Fly, which raises indigenous Mediterranean fruit flies and sterilizes them.

Bio-Fly, a subsidiary of BioBee, was founded “for the purpose of developing and supplying biological control solutions for the Mediterranean fruit fly (Medfly) and other pests, using the Sterile Insect Technique,” according to the outfit's website. The newspaper Haaretz says that the Israeli Atomic Energy Commission supervises the radioactive sterilization of the fruit flies while the kibbutz has a collaborative agreement with the Palestinian Authority, Jordan, and several Mediterranean governments for the distribution of the sterile flies. The company has a mass rearing facility and supplies sterilized male pupae, as well as sterile male flies for dispersal in agricultural fields. The latest swarm of flies were scattered along the border areas of Croatia and Bosnia. Normally, about 15 million sterilized pupae are produced each week at Bio-Fly. The sale to Croatia was over a third of a billion flies, so perhaps production has ramped up recently. (The 380 million flies were weighed, not individually counted.) By the way, the reason that only male fruit flies are sold is that it prevents a potential disaster if some flies are not effectively sterilized - no egg-layers are shipped abroad. The sterile males successfully mate with indigenous females who then remain infertile their entire week-long adult life.

|

I was surprised that the Croatian tourist haven has a big tropical fruit industry. The coast is mostly craggy with mountains that encroach upon the sea. Almost everywhere along the coast, there isn't much more than a skinny (but inviting) beach. But when I approached the Croatian coast from Sarajevo, driving south through Bosnia, a friend and I found ourselves on the broad Neretva Delta - a warm lowlands of rich soil and dense gardens and groves. It was quite a switch from the barren stone-filled hills to the north. Until the moment Neretva's river valley opened before me, I was unaware of Croatia's huge citrus industry. But as a Mediterranean country, Croatia's burgeoning fruit-producing area suffers from the Medfly. (For more, and some great pictures, see the UN's FAO report about Croatia's fruit fly pests.)

Despite the flies, I was enthralled with the orange groves - something I missed since my Florida beekeeping days. Seeing all these small acreages owned by independent farmers who peddle their fruits and veggies at roadside stands was a slightly nostalgic trip back in time. I didn't see any honey bees in the groves, but my trip was in October, not March, so the trees were not blooming. Migratory beekeepers would have moved their colonies north in early summer. The bees would not have been back until perhaps November. But when they did return, the beekeepers would not have to deal with clouds of malathion drifting over their bees, thanks to 380,000,000 imported radioactive male fruit flies.

|

|

No Cheery Welcome for the Beetles

"Ladies and gentlemen, The Beetles!" ** That's how Ed Sullivan introduced John, Paul, George and Ringo to the American public. The introduction was followed by a lot of screaming, some disruptive noise on Ed's stage, and general hair-pulling by the audience. Not so different when The Hive Beetles entered the world stage. The latest stop on their uncelebrated global tour is southern Europe.

A friend in Europe wrote to me, wanted to know my thoughts about these new beetles. They were found this year in southern Italy. According to the Invasive Species Compendium, hive beetles (Aethina tumida) "are considered to be a minor pest in [South] Africa, but a major problem in areas where they have been introduced." So far, the beetles have been introduced to the USA, Canada, Jamaica, Australia, Italy, and possibly Egypt. Indeed, they are on a world tour. They are not very active here in Canada - I think it is too cold, at least out on the prairies. The hive beetles either flew across the border from the states (They can fly a few kilometres at a time.); or, more likely, they arrived on imported equipment a few times, but never gained permanent residency status. I have only seen hive beetles once, on a trip to Florida. So, I am not an expert. However, I told my correspondent what I know from my perspective, but it is not from first-hand experience. (Lack of experience has never stopped me before.)

The hive beetle is certainly an ugly and nasty insect - most of the damage is done during its larvae stage - creepy, densely populated worms that cause a lot of trouble. No one wants the pest in their hives. They destroy comb equipment and make a big mess. When they were first found in the USA, beekeepers and researchers were frightened. Bee equipment was quarantined and it was difficult to get approvals to move between states. Equipment was sometimes burned by government inspectors. Scary movies were shown at beekeepers' meetings. (I know - I sat through one such thriller here in Alberta.) Then people settled down and the hive beetle is now considered a minor (albeit grotesque) pest. But the initial infestations were an opportunity for excitement. I think it will follow a similar trajectory in Europe: initial fear and panic, oppressive regulations, then finally acceptance and control. This was precisely the story of the honeybee tracheal mite - HTM caused the initial Canadian-American border closure while some petty bureaucrats did their best to cow the beekeepers. Today no one seems to even look for HTM.

Beekeepers will learn a few tricks that will reduce the problem. Most beekeepers will be annoyed by hive beetles, but few (if any) will be put out of business. Some of my friends and family have commercial bee businesses in central Florida which has had substantial populations of the beetles for a few years. Hive beetles are not their biggest headache. Here are some of the tips they have found to keep things that way:

- Keep things clean. The beetles can infest stacks of old combs - devouring pollen, tunneling, burrowing, defecating, and making a really fine mess of things. Stacks of equipment should be covered. Floors should be clean - a lot of beekeepers are sloppy, allowing wax and pollen debris to build up in the workshops - these harbour and feed the hive beetles. If you are a messy beekeeper, your days may be numbered.

- Handle honey promptly. If honey is taken from the bees and the boxes and combs are allowed to sit inside a shed for a few days, hive beetles may move in. The result is a slimy mess that ruins the honey and the equipment. The beekeeper should process honey right away and not wait - that's always good practice anyway. If you are a procrastinator, your days as a beekeeper may be numbered.

- Keep bee colonies strong. The small hive beetle does not kill bees or eat brood, but can wreck a weak colony that does not defend itself. The bees may be so distraught that they abscond (abandon) their nest. Good healthy colonies don't have serious problems, but a few beetles may hide in hive crevices and if the colony becomes weak, queenless, or neglected by the beekeeper, the population of hive beetles swells. The best defence against hive beetles is a strong colony of bees. If you are a negligent beekeeper, your days are certainly numbered.

There are a few other tricks - beekeepers in susceptible areas may set traps, use chemicals (see the links below), or assist specific nematodes (tiny worms) in the soil in the apiary to act as guards against infiltration.

For more, here are a few links to follow:

- Wikipedia (this is actually a good reliable article): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Small_hive_beetle

- Hive Beetle in Europe (detailed PDF information sheet) https://secure.fera.defra.gov.uk/beebase/downloadDocument.cfm?id=17

- Managing Small Hive Beetles (this page was written in November 2014, so it is very up to date): http://www.extension.org/pages/60425/managing-small-hive-beetles

** Yes, I know. The English Beatles misspelled their name, but indulge me, OK?

|

Packing Honey Combs

With a break in the weather, my kids and I made a trip down to the farm. It is in Vulcan County, aptly named for heat. Vulcan can be really, really hot is the summer. But it is late fall and we've already seen a few days of minus 20! However, the past couple of days were pleasant, so my two youngest and I went to the countryside to give my older daughter a hand at packing honey. Erika and her husband have owned, managed, and operated our old farm for the past four years. This season was good. The couple are running Canada's largest comb honey farm, producing tens of thousands of combs a year. (Sorry buyers, they are completely booked and sold out already.)

Today I am repeating some pictures I put on line last year. I didn't take photos this weekend, but not much has changed in the past year. (Except the younger kids are taller.) These pictures will give you a tiny peak inside the comb honey packing shop.

|

|

|

|

|

Buzzing Out-of-Sync

If flowers bloom a month earlier than usual - as they reportedly did last year in Maryland - what does that mean for bees? According to Will Plants and Pollinators Get Out of Sync? it could mean trouble. The story appears on NASA's website and explains how plants and pollinators have co-evolved: "the two species time their cycles to coincide, for example, insects maturing from larva to adult precisely when nectar flows begin."

Before we consider the implications, I'd like to dismiss the notion that the species got together over beers one evening to "time their cycles." As the NASA correspondent undoubtedly knows, cycle-timing is entirely an accident of nature, an accumulation of evolutionary mishaps that include genetic mutations and selection. Rather than coincidental planning, pollination synchronization results from an exclusionary rejection. If, for example, a plant suffers a mutation which results in early blooming (say, a rewrite of the base pair in a gene that produces a protein benefiting from heat stimulation) and if no bees are around at the new earlier flowering time, the flower simply does not reproduce. There are no seeds and there is no next generation of similarly off-sync flowering plants. However, if there is also a type of pollinator bees that coincidentally suffers a genetic mutation resulting in an ability to rapidly build a large spring population, the mutated flower will have pollinators available to "meet up" with it. That plant will produce similarly inclined seeds and the bee colony with its tendency to build an early spring population will also thrive and spawn more early-risers.

Mutations are rare, nevertheless mutual coincidental genetic disruptions happen frequently amongst the billions of creatures involved. It's a numbers game and the numbers are big. Each year, about one in ten million of each DNA base unit is altered during replication. This happens by exposure to natural radiation or chemical hazards. If there are over a hundred million individual seeds in a field (the number of alfalfa seeds produced in a quarter-section, for example), each year ten seeds in the field will suffer genetic damage to the coding affecting the proteins that result in early flowering. So, it does happen - and at a surprisingly fast rate when we consider the billions and billions of seeds produced each season around the world. This is how plant scientists genetically alter plants (unless they are "genetically engineering" by manipulating bits of genetic code). Plant scientists expose millions of seeds to high-level radiation, resulting in accelerated rates of mutation. Then they grow the resulting plants and measure the results: A brighter colour? A longer stem? A tastier fruit? Nature plays this same game over a longer period of time. Wild flowers in meadows and seeds in fields are nature's genetic laboratory. (If you would like to understand mutation rates, this easy article by Toronto professor Larry Moran discusses estimating the rate of human mutations - which average about 150 genetic mutations per person each generation.)

What is the effect of a warmer climate on plant pollination? First, we know that temperature is not the only factor that determines when a plant will bloom. It is not even the most important factor. Length of day is. Photoperiodism is a fascinating subject. Plants have 15 different types of cell receptor that sense light. Humans, by the way, have just 3 and ours are stuck inside our eyeballs' retinas - a plant's eyes cover its entire body. The thing that triggers blossoming is the period of time between the last flash of "far red" at the time of the setting sun and the next full spectrum sunshine, the following morning. Greenhouse managers know this and they sometimes toy with the plants' transducers, forcing off-season flowering, by exposing plants to artificial light.

But for this discussion, let's assume ambient temperature actually triggers flowering - as it does in some plants. Will flowers and bees become "out of sync" because of climate change? According to this Independent newspaper article, "Higher temperatures may result in fewer bees, scientists claim", the future is dire. "This is because the more out-of-sync pollinators and plants become, the more difficult it will be for each to find opportunities for pollination – potentially threatening a wide variety of plants, including crops of seeds or fruits, most of which depend on pollination," says the Independent, adding "it will raise fears that popular foods such as apples and pears could be affected." However, those popular foods (Pears are popular? Not in our house.) will survive because the orchard managers contract beekeepers to supply honey bees. If the season slides forward, the beekeeper will adjust his schedule, developing stronger colonies earlier. This has already happened in California's almond groves where big colonies are required in February and beekeepers react by stimulating their bees in early January. Farmers will somehow manage. The ever-popular Bartlett pear will remain a staple food (in homes other than ours*). But wild bees and birds might not be so lucky, according to both common sense and the NASA article.

Hummingbirds are at risk. "Honeybees aren't the only pollinators affected by climate change. Hummingbirds and other migratory pollinators may be even more susceptible if their seasonal migrations become out of sync with the flowering and nectar availability in their breeding habitat," says NASA's Earth Observatory website. I think the bottom line to this story is that humans, driven by profit and self-interest, will continue to enjoy juicy pears for generations to come, but the rest of the animal kingdom will be left to survive by the luck of evolutionary adaptation. Some species will adjust to the warmer climate, others will join the ranks of the extinct. Beekeepers will become more adept at manipulating colony populations to provide bees for commercially valuable crops while roadside asters (as seen in today's photo, above) will mutate or perish. If man's role in the changing environment fascinates you, you may like to read a piece I wrote for my Earth sciences blog, at this site.

(* We do eat the occasional pear. It's just hard to describe the fruit as popular.)

|

Dead Swiss Bees

Something odd was killing bees in Switzerland. It was sudden. It was peculiar. It was devastating. This past spring - in April, 2014 - beekeepers in the Zäziwil and Möschberg region found almost 200 colonies dying. They quickly recognized signs of poisoning. Local farmers denied using neonicotinoids or other insecticides. They were honest. They had not. Yet nearby bees were in rough shape.

Swiss investigators moved in. They demanded the farmers' receipts. What had the farmers bought? What had they used? The investigators discovered that orchards in the area had been treated with the fungicide Folpet, which is allowed in Switzerland. Folpet is not an insecticide, it is a pesticide. The pests that it attacks are fungi. This fungicide is closely related to a much older fungicide, captan, which some of my more ancient readers will recall from their childhood. I do. I fondly remember running in a white cloud of dust, chasing after the family tractor as my father planted long rows of captan-treated seed potatoes. Because of the treatment, our potatoes did not suffer from Rhizoctonia, and neither did I. Recently, the EPA stated that captan and its sister fungicide Folpet are non-carcinogenic, except in "high doses and prolonged exposure." Interesting. Used in orchards, captan and Folpet enhance the outer beauty of fruits - making them spot-free and shiny. This may be why I was allowed to follow in captan's shadow when I was a child.

I have brought you no closer to finding the Swiss bees' killers. But we've learned something about the fungicide Folpet. And so did the Swiss inspectors. They learned that the Folpet came from a factory is Israel. The factory also makes a non-neonicotinoid insecticide called Fipronil, which is banned in Switzerland. Just before making the Swiss batch of the fungicide, the factory had filled American and Brazilian orders for Fipronil. Allegedly there was still some insecticide in the factory's system when the fungicide was made. It seems that the equipment was not cleaned before they started to produce Folpet. The Swiss government removed the suspect batches from their local market.

This story points out how tough it is to avoid poisoning our honey bees. The farmers were not using insecticides (or so they thought); the Swiss government had outlawed Fipronil and it could not enter the country (or so they thought); and the bees were pollinating fruit trees and collecting life-sustaining pollen (or so they thought). If this is the story in its entirety, it also suggests that even a small amount of poison (the residual left in a system when the factory switched from fungicide to insecticide) can kill a lot of bees.

|

A New Origin for the Bee?

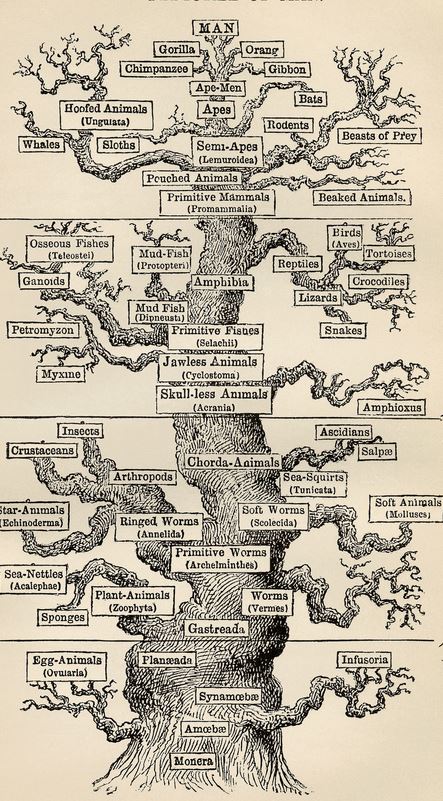

Years ago, we learned that honey bees developed in Africa, then spread north and evolved into different subspecies. It is not surprising that the bee could adapt to the much colder northern climates - you don't even need to accept evolutionary science to see how that might work. With moderate genetic mutations from damaging gamma rays or localized environmental hazards, changes occur. With vast and rapidly reproducing populations such as bees, some mutations inevitably are beneficial to survival. In the presumed case of bees out of Africa, as bees slowly migrated north, the most cold-hardy descendants reproduced. From Africa's adansonii or scutellata (or their earlier representatives), descendants became Europe's mellifera, ligustica, caucasica, and carnica. These are the black bee, the Italian, the Caucasian, and the Carniolan respectively. But this simplified collection leaves out a host of other non-African races - the Middle Eastern anatoliaca, syriaca, lamarckii and meda, for some examples.

Did the honey bee originate in Africa? The out of Africa idea was developed a hundred years ago and was based on phenotypical traits (physically visible and measurable characteristics) and the assumed effects of geography and climate on the bees' divergences. But now we are not so certain. In 1992, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was analyzed from 68 colonies in ten different regions. The scientists found 19 different subspecies represented by the mtDNA. On the basis of their best fit "Tree of Life" model, they clumped these into three different clades, or branches. These lineages are African, Mediterranean, and European. But these scientists had a surprising result. They found that the oldest mitochondria could be traced to the Mediterranean branch while the African branch showed greater change. They surmised that the original dispersion of honey bees was from the Middle East: "The pattern of spatial structuring suggests the Middle East as the centre of dispersion of the species." This result, from "Evolutionary history of the honey bee Apis mellifera inferred from mitochondrial DNA analysis", published in Molecular Ecology also included the suggestion that the present subspecies divided less than one million years ago, as indicated by a 2% variation in the relevant mitochondria DNA.

The Middle East origin for honey bees was a surprising result. It went against prevailing notions, so other researchers were reluctant to accept the findings. However, in August of this year, confirming evidence was published. Using a larger sample set (140 honey bee genomes and 8.3 million SNPs) and more modern equipment, results were published in Nature Genetics in late August. Matthew Webster, researcher at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Microbiology, Uppsala University (in Sweden) says, "The evolutionary tree we constructed from genome sequences does not support an origin in Africa." Instead, our modern honey bee originated from common ancestors in the Near East and began a rapid dispersion about 300,000 years ago into Europe and Africa.

You may wonder if the study of the bees' genetic tree has much relevance for today's beekeeper. Here is something to note. Almost as a passing thought, researcher Matthew Webster adds, "In contrast to other domestic species, management of honeybees seems to have increased levels of genetic variation by mixing bees from different parts of the world. The findings may also indicate that high levels of inbreeding are not a major cause of global colony losses." We can trust Webster on the factual part of this discovery - he is telling us that his world-wide samples of kept honey bees are more genetically diverse than other domestic species (i.e., pigs, sheep, goats, bananas, potatoes). It should then follow, he suggests, that Colony Collapse Disorder is not due to inbreeding of honey bees. Instead, it is more likely that some other factors are culpable in the disappearing disease that sporadically hits apiaries.

|

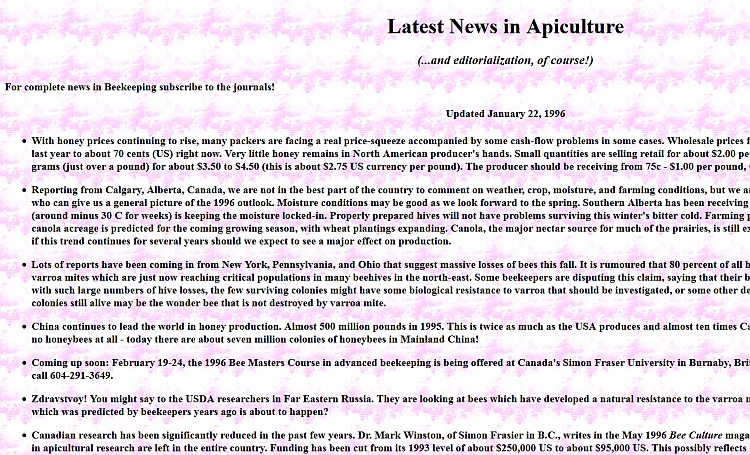

A Long Time Bloggin'

Web logs - blogs - have been around for 20 years this month. That is according to this piece from (where else?) someone's blog. I have been writing this bee blog - these pages about the politics and science behind beekeeping - for 19 years. I started in October 1995, and from the start, my pages included a ranting and raving page similar to a modern blog. The image above shows you what my January 1996 'bee blog' looked like. When I began this exercise, I was in my 30s, had mostly dark hair, and quite a lot of enthusiasm. As best I can tell, the blog you are reading right now might be the first one ever started. In case you missed that start-up, here is a link to the Beekeeping News Page in my archives.

What good is a bee blog? There is a certain voyeuristic element to reading a beekeeping blog. It is like sneaking a peak under someone else's hive cover. Except with a bee blog, the beekeeper is tipping the lid for you. Today there are easily 10,000 personal beekeeping sites and probably a thousand of those have blogs. Many of them are great. Part a beekeeper's education is to study the tricks, tips, and thoughts of other beekeepers. And then borrow what makes sense. You won't get a lot of clues from my blog here as this is more news and opines than practical bee culture. But if it is the latter you are after, you will find my book, Bad Beekeeping, is stuffed full of beekeeping advice. Not that any of it is good advice - but it is all interesting.

|

The Tired Honey Man

Friends just back from Uzbekistan shared this photo with me. The gentleman is selling honey and he doesn't seem too happy about it. We'll get to that in a moment. First, what is Uzbekistan? It's a place on the other side of the planet. From me. If you live in Uzbekistan, then I guess I'm the one on the other side. Uzbeks were taken over by the Russian Empire 200 years ago, then fell under Soviet rule for a couple of generations. One legacy is the Cyrillic script you see almost everywhere. Another legacy is incredible pollution and general despair in daily life. The country is ruled by a "strong man" who enforces allegiance and law and order in an otherwise unruly nation. Uzbekistan has the odd distinction of having more Stans as neighbours than any other place on Earth - its five abutting Stans are Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan. Uzbekistan is generally perceived as dusty, repressed, depressed, and difficult. I suppose that's not entirely unfair. The country has slavery, pollution and water problems.

Uzbekistan is cursed with a near-perfect cotton-growing climate. Cotton is the main business in that country, but the fiber has a brutal history. It is tough to grow and in Uzbekistan, cotton is mostly picked by hand. Cotton picking, of course, contributed to slavery in America and elsewhere. In Uzbekistan, Human Rights Watch says that as many as 2,000,000 men, women, and children will be used as slaves to harvest this month's cotton crop. The government says it is everyone's national duty to pick cotton. Well, not everyone - just the poor. The result of their national duty is the export of over a billion dollars worth of cotton. It props up the poor country's economy and keeps the leader in power. But people die in the fields, according to Human Rights Watch, while performing their national duty - unpaid forced labour.

Then there is the water. Cotton thrives in Uzbekistan's desert climate - if it is irrigated and heavily fertilized. Water is diverted from entering the Aral Sea and directed into the cotton fields. This has quickly turned the world's 4th largest salt lake into a puddle. Once half the size of England, almost all of Aral has disappeared in the past 40 years. The environmental disaster began in the era of the Russian Empire, but the Soviet overlords brought industrial-scale cotton-growing and landscape degradation to an art.

Along with pillaging the water, there is ubiquitous pollution. Typical for huge monoculture plantations, cotton is targeted by weevils and other evils. The solution is harsh poison - not systemic insecticides, but aerial and boom-spray applications of cancer-causing insecticides. Further, the continuous cropping is sustained only by industrially-produced fertilizer which has polluted what is left of rivers and lakes in the country. The air, I am told, has a stench of poison everywhere. There is little escape for ordinary folks - conscription, dust, and pollution are the reality.

|

Which leads me back to the honey man in today's picture. He doesn't seem very enthusiastic does he? But who could be in his position? Undoubtedly his bees have also tasted the chemicals in the air. It is hard going for Uzbekistan's beekeepers. The government - the same one responsible for the poisons and the slavery - is expanding beekeeping by seeking bee equipment. Maybe it is some sort of 5-year plan. I imagine their plans will compete against beekeepers such as the one shown above. Last year, the government estimated honey production at about 4 million pounds. They think they can expand it. Much honey is sold in recycled containers, including the Nutella jar you see here. Plastic wrap is often used for lids. There is no fault in that - beekeepers do what they must to survive. Including gloomily retailing honey at the big Tashkent market as the honey man pictured above is doing. He may be exhausted, he may be tired. Or he may be thinking about his trip nexy week into the countryside cotton fields in the back of a big transport truck. Slave labour - the national duty - for his country's kings of cotton.

|

Who is the Saint?

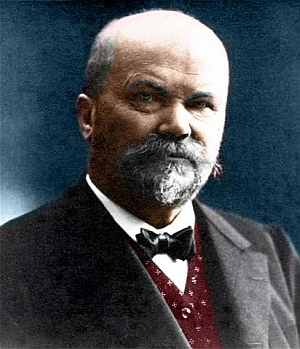

On this day in 1970, Norman Borlaug accepted his Nobel Peace Prize. You probably never heard of him. A few days ago, I read an interesting piece in an old New York Times column, written by author/philosopher Steven Pinker. He had a few words to say about Mr Borlaug. I'll tell you what Steven Pinker said, but you can read the story yourself - it is at this address.

Steven Pinker was writing about how we perceive morality. He noted that if we were asked to pick the most moral person from this group - Mother Teresa, Bill Gates, and Norman Borlaug - we would almost all choose the saintly little lady who went to India. We might reject the billionaire who was accused of monopolizing software. And, about Norman Borlaug, we would likely ask "Norman who?" Mother Teresa moved from Kosovo to Calcutta, tended the poor, sick, and weak, and developed the Missionaries of Charity. She is the obvious choice and directly helped thousands. But Bill Gates adopted the problems of the developing world - malaria, among others - and has (somewhat) quietly contributed billions to find solutions. His work has possibly saved millions of lives. Then there is Norman who. His Nobel Peace Prize recognized his almost invisible work that revolutionized agriculture and invented the Green Revolution. By some accounts, Borlaug is credited with saving a billion people from cruel slow desperate deaths by starvation. A billion lives - that's more than anyone else in history.

Of course it is unfair to ask who among the three is the most moral without presenting a definition of morality. But on the strength of saving human lives and reducing suffering, Norman Borlaug's contributions were astounding. During the 1960s, dire predictions of the eminent tragic starvation of the majority of Chinese, Indians, and Africans was prognosticated by the most knowledgeable minds. But it didn't happen. Norman Borlaug, an American geneticist, applied the latest ideas in bio-engineering and found a way to feed the billions. India, once deemed to decay in misery and starvation, now has 1.1 billion souls and is a net exporter of food.

In the 1950s, Norman Borlaug worked mostly with wheat, genetically dwarfing the plant so it wasn't spindly and prone to falling over and losing its seeds in the field. He dramatically increased seeds per stalk and developed resistance to disease. The result was wheat that revolutionized food production in Mexico (where he did most of his research), and Pakistan and India which were becoming desperate for the help his wheat brought.

Why write about better farming and morality on a bee blog? Occasionally it is good to commemorate unselfish contributors such as Borlaug. Early in his career, Borlaug was employed by DuPont. He was offered twice the salary to stay with them, but he left for an NGO in Mexico instead. His young family would have appreciated the money. But he took the job that he thought could make the most impact and help the most people. It is also important to occasionally remember that without genetic manipulation and the application of science to solve a desperate problem, a billion people would have died. Today we find a vocal group of wealthy and comfortable folks (wealthy and comfortable by world standards) who are trying to stop scientific progress that could - for one example - allow a genetically altered form of rice to provide nutrition that would save a million children from blindness. Some well-off people with no risk for themselves or their children of suffering vitamin deficiency in America or Europe nevertheless campaign to prevent golden rice from being used in India. It is a twisted sense of smug self-interest that causes this tragedy. A billion people are lucky such people were not able to stop Norman Borlaug's work fifty years ago.

No longer almost free

|

At a get together with a small group of beekeepers, we all started bugging one of the fellows about the price of his honey. At $10/kilo (less than $5/pound) one lady figured we could do well buying his entire crop and selling it ourselves. She might - she's a born sales person. Me, not so much. But it got me thinking about the price of honey. And how hard it is for a beekeeper to decide how much to get for the stuff. Many beekeepers, it seems, are embarrassed to ask for the market price for their honey. To them, almost free is almost too much.

Honey has reached a record high price in North America. It has never been worth more. US bees are increasingly diverted into pollination, leaving fewer to gather honey. Much honey is imported into the states (2/3 of all US-consumed honey is imported) but the foreign sources are getting harder to buy because of growing world-wide prosperity - countries that used to export their honey now use it locally. And some countries - such as China, for example - have begun to buy North American honey. I know, first hand, that this is true. So honey prices are up. But I was still shocked to see how big the price increases have been.

Bee Culture magazine has had a group of faithful honey vendors provide prices on a monthly basis for decades. In September 2006, one could sell packaged cases of jars at a wholesale price of $2.80 per pound. Eight years later, the average price for the honey has almost doubled, to $4.98 per pound. Of course, that is filtered and packed and labeled and ready for the store. The USDA reports that the wholesale bulk price (in drums or totes) has more than doubled - from $1.03 per pound to $2.12 per pound in 2013. So, if you are selling a few hundred pounds of your finest wares, check prices at the local stores, tell your customers that your honey is better than the store stuff (It probably is.) and don't be shy about getting the market price for your effort.

Caught in the middle

Are they staying or are they going? The Globe and Mail, "Canada's newspaper," has an editorial written by Margaret Wente. She calls her piece "Caught in the Middle of the Bee War" and it is about the vanishing honey bees. This is not the first time Ms Wente has written about bees. The first such story that I can remember described her husband's beekeeping adventures and it appeared around 2004. It was an unusual piece because it was quite funny - Margaret Wente usually shares more serious opinions about politics and economics. Yesterday's column was fittingly Wente, commenting on the politics of disappearing honey bees.

The Globe and Mail piece surprised me. It begins with the usual "bees are going extinct" and "neonicotinoids are to blame," but then Ms Wente seems to indicate that she believes neither. Which is refreshing, because managed colonies of bees are certainly not going extinct. World-wide, the number of kept hives is 45% higher than it was 50 years ago. Since Colony Collapse Disorder was first noticed (around 2006), and since neonics became widespread (also around 2006), the number of bees in North America increased from 2.2 million colonies to 2.4 million today. Not exactly extinction. Nor is it likely that neonicotinoids are playing the leading role where sudden colony collapse is noticed. I say this because I live in Alberta, a place where neonics are used extensively, and Albertans have not suffered colony collapse. Not yet, anyway.

The column by Ms Wente mentions the Ontario lawsuit. The suit pits two Ontario bee outfits against Bayer, a manufacturer of neonicotinoids. But it was set up as an "opt-out" class action suit. Beekeepers are automatically part of the suit, unless they expressly ask to be left out. Here is what the Globe and Mail piece says about Alberta: "Alberta’s beekeepers, which produce nearly half of Canada’s honey, aren't joining the lawsuit. They say the new seed treatments actually reduce the bees exposure to harmful pesticides."

A bit more from the Globe's piece:

"There's no doubt that something is ailing the bees, or at least some of them.

Ontario has been hit particularly hard by bee die-offs lately. But a lot of experts

say the problem isn't neonics. In Australia, the bee population is stable even

though neonics have been in use there for years. The Australian regulator recently

reported that neonics are better for crops and the environment than the products

they replaced."

Educating the humans

|

Killer bees used to be big news. Enough people are nervous around bees (even the pleasant, nearly harmless, garden bees) that the idea of massive stings is terrifying. "Bee venom is a cocktail of biologically active components that are designed to inflict pain. The honey bee stings only defensively — they don't try to kill, they try to educate,” says May Berenbaum, a professor at the University of Illinois. Unfortunately, the Africanized honey bee sometimes forgets this important rule. Yesterday, four landscapers working at a southern Arizona house were attacked. One man died. The Douglas Fire Department Chief reported, “A witness said his face and neck were covered with bees." That 32-year-old man died of cardiac arrest. Another man, stung more than a hundred times, was treated at the local hospital and released. The workers were part of a program teaching work skills to developmentally challenged adults. Our thoughts are with the families and friends of the people attacked and with the directors of this worthwhile charity.

It is claimed that the offending bees came from a nest of 800,000, according to the press. If that is true, it would be ten times larger than any colony I ever heard of. Most likely, someone miscopied 80,000 bees (which would still be an enormous hive) and wrote 800,000 and that numbered has been repeated over and over again in all the news coverage, all of which seem to buy the same story and repeat the same mistakes.

Once an error is published, it takes on a life of its own and is almost impossible to eradicate. If you look at this link, you can see how the number was picked up and unquestionably reproduced. The Weather Channel headlined with the absurdity "Arizona Landscaper Dies After 800000 Bees Attack" - only a small percentage of any hive attacks. Isn't it enough to report the fact that hundreds of bees attacked the unfortunate workers? The Weather Channel headline is either hyperbolic exaggeration or careless fact-checking - both of which are unforgivable errors from an outfit that reports the weather. Meanwhile, the New York Daily rounded up: Nearly 1 million bees swarm Arizona men, killing one. Others repeating the 800,000 number include Gawker, Inquisitr, United Press International, The Mirror, and NBC News. Interestingly, a reporter closest to the source of the attack (Tucson News Now) wrote, "One person is dead and several others are recovering from bee stings after a huge swarm of about 300,000 bees attacked landscapers working outside a home in Douglas." Hours after the story initially ran, CBS has written, "A swarm of about 300,000 bees killed one landscaper and critically injured another... The [Douglas Fire] Station initially reported that an estimated 800,000 bees were involved in the attack." Better, but still not right. And why didn't the initial reporter ask the fire department which entomologist at the station counted the bees?

Deaths from Africanized honey bees are still rare enough to make front page news as this story did on Canada's National Post, UK's Telegraph (which accompanied their story with a picture of a tiny cluster of bees in a tree), and the other sources (or repeaters) that I already mentioned. When the Africanized bee first arrived in the USA, there were concerns that thousands of deaths would quickly follow. This angst was led by an overly eager press and encouraged by researchers (some seeking grants to study the problem) who often were inexperienced around bees. To the novice, three bees chasing after an exposed face may elicit thoughts of a fifth apocalypse horseman. Place a young, untested grad student in Brazil next to an Africanized swarm, and he will live to tell some scary stories about the bees. So, for a few years in the mid-1970s, Africanized bees dominated the press whenever honey bees were mentioned. Today, of course, unfounded rumours of bee extinction lead the news stories. I guess that's a bit more upbeat than the tales of wonton destruction and fears the Killer Bees once conjured. Nevertheless, exaggeration and hyperbole very quickly become tedious.

Bees as a small business

A lot of North American beekeepers operate huge operations. These days, 2,000 colonies is about average for a commercial operation. Help is usually imported seasonally and the beekeeper/owner is sometimes a bookkeeper/trucker who has more than a veil and gloves between himself and his bees. I asked one of these operators about this. He told me that's the only way he can keep bees full time and feed his family. He is probably right.

Real beekeeping - shirtless, shoeless, without gloves and veil - is mostly confined to sideliners. This includes operations like the 26 hives run by actor Morgan Freeman (who probably doesn't need the extra honey money). And it includes perhaps a thousand or so others in the USA and Canada who run 20 to 100 hives on weekends. For these folks, the bees (when profitable) provide a bit of income, but are mostly kept as a hobby. However, I know of a few others who keep a small number of hives to supplement retirement income.

I have great respect for a beekeeper in my area who retired at age 45 from a rather good job that had him traveling all over the world. He had saved some money, but certainly did not have enough money to live on. But he was determined not to work for anyone ever again. For the past 25 years, he has been keeping about 50 hives of bees. Each year he makes about 8,000 pounds of honey. He owns one small truck, makes his own equipment, hires no one, sells all the honey out his backdoor, and grosses $40,000 a year. With expenses at around $10,000, the profit nicely enhances his unpretentious lifestyle and supplements his modest income from retirement investments. And he genuinely enjoys beekeeping.

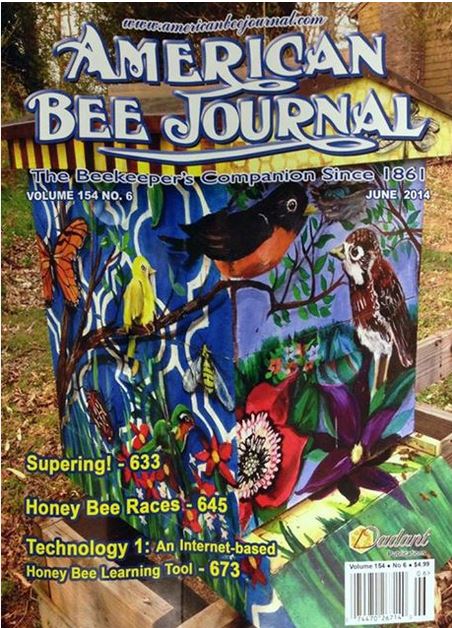

There is another beekeeper, this one a world away in northern Russia, who wrote a short interesting piece in a recent issue of American Bee Journal. This fellow, age 63, is a retired professor. He has been running bees for a long time. He has a lot of experience. He stays fit, enjoys the outdoors, and makes a complementary income from his 60 colonies. About the numbers, he writes:

"One ton of honey I produce yearly for about $6 for one pound.

In addition, I sell 10-20 overwintered colonies, about 100 kg (220 lbs)

of sealed [comb] honey and about 50 kg of a homemade mixture

of pollen and honey. So it all adds up to about US $20,000 of

gross income. I net about $17,000 a year."

Both of these beekeepers are retired from professional careers and have found satisfaction and a modest income from keeping a small number of colonies of bees. It can be done. I suppose it can also be done by beekeepers who decide to retire from 40 years of running 2,000 colonies - though most of these folks can not dismount from their behemoth bee businesses (and associated obligations and mortgages) and will never get back to the small scale endeavours that would evince more pleasure than meeting pollination deadlines and payrolls.

Hives as Art

|

North Americans are missing a great canvas. The beehive. Solid, often white and publicly visible, it should be used by artists more often. I've been lucky enough to work hives in the USA, Canada, Mexico, Europe, and South America. Surprisingly, the most decorated colonies are in one of the most traditional cultures. Slovenia - a tiny country wedged between Italy, Austria, and Croatia - is known for its somber, hard-working folks. Slovenians honour seriousness. They tend towards understatement and practical good sense in their homes, architecture, and businesses. One might think them dour but they sure have some funky beehives. Like the one to your left. Hideous, isn't it? It shows a woman - the village gossip - with her tongue against the sharpening stone, held in place by devils. The hive panel, called a panjske končnice, is nailed to the front of the hive, near the hive entrance. It helps the bees find their home. Slovenian hives are sometimes stacked atop each other, sometimes squeezed onto semi-permanent trailers, sometimes lined up tightly on the porch near the kitchen door. Without colourful markers, bees could easily flounder. The entrance panels serve a dual purpose - they keep both bees and souls from being lost. Traditional thought remains strong in Slovenia. These message boards are still pretty common, as are their moral messages.

|

In Chile, my friend Francisco Rey stocks queen-mating nucs like the ones in the next picture. He told me that he turns his helpers loose with paints and brushes, telling them, "Divertirse!" And they do have fun. The only instruction is to be creative. The Chilean paint job serves the same function as the Slovenian entrance board - to help bees find their way home. This, as you likely know, is particularly important when young queens are on their nuptial flights. It would be too easy to end up in the wrong nuc if the boxes looked like houses in Smalltown, Indiana. And residents would be like so many party girls coming home late on a weekend night, not quite sure where they belong. (For that, the Slovenians also have an appropriate hive panel.)

|

Meanwhile, in North America, we aren't much into hive art. I think that's a legacy of our puritanic heritage. Functional and practical and white are preferred. I am just as guilty as most beekeepers here, as you can see in the picture below, from an incredibly dull bee yard we have in Vulcan County, Alberta, Canada. The bees might make more honey if their boxes had eccentric colours and if the hives were aligned less straightly. But don't they look great?

|

Exciting beehives are rare on this continent. It is so uncommon, in fact, that painted hives make the news. At least, beekeeping news. American Bee Journal featured artist Jill Sanders' great hive art on their June, 2014, magazine cover. And out at UCLA Davis, Diane Ullman's half-acre bee garden, the Haagen-Dazs Honey Bee Haven, has a whole bunch of interestingly painted beehives. In this case, too, the painted bee boxes are cool enough to be written about, as you will see if you follow this link. I like the colourful hives, they certainly help bees find their homes, but we North Americans mostly employ drab monotonous unaesthetic hives, rarely straying from "white" as a fashion statement.

|

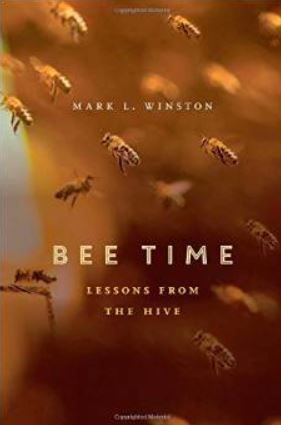

Lessons from the Hive

In the mood for a good read? Looking for a holiday gift? Mark Winston's latest book, Bee Time: Lessons from the Hive, is as good as his other bee-related books. Which means it is very, very good. I haven't read it cover-to-cover yet, but I have jumped around a bit like a bee in clover - so much to take it! Those of you who have read some of my reviews on other books (and movies) know that I can be pretty harsh. So, if I tell you that this book is worth more than the $20 Amazon is asking, you know that it is.

It's a personal story. I especially appreciated the last segment of the book, the Epilogue - Walking Out of the Apiary. But I will quote from the penultimate section, from Winston's chapter called Lessons from the Hive. It'll give you a bit of the flavour of the book:

"Bees can be the richest of guides to the most personal understandings about who we are and the consequences of the choices we make in inhabiting the environment around us. Conversations with beekeepers about how they are affected by their time in the bee yard show a remarkable consistency. Words like "calming," "peaceful," and "meditative" come up over and over again, and beekeepers visibly relax when talking about their bees." - Mark Winston, 2014

Bees Back Up on their Knees?

In today's unlikely Op-Ed article in the New York Times: Are Bees Back up on their Knees? beekeeper Noah Wilson-Rich makes the case that the worst of the mysterious colony collapse syndrome may be over. He reviews what many of us have been saying for a long time - this isn't the first time bees 'disappeared' from their hives. This fact does not reduce the seriousness of the current malady nor does it mitigate the expensive - sometimes bankrupting - losses many beekeepers suffered in the past few years. However, Noah reminds us that unexplained collapses occurred in "the years 950, 992 and 1443, when Ireland's beekeepers noted remarkably high mortality events. Reports from the Cache Valley in Utah in 1903 described thousands of dead hives; around the same time, the Isle of Wight in England faced a near total loss of honeybees." My father told me similar stories of almost totally empty hives a couple of seasons in the 1950s in Pennsylvania and New York. Anyway, the New York Times piece is an interesting read and gives a little balance to today's situation. As the editorial points out, all is not well and rosy, but neither is it all dire and death. The writer makes valid points about the difficulty commercial beekeepers face in a world of diseases, chemicals, and habitat loss.

|

Sweet New Year!

Shanah Tovah! Rosh Hashanah, or the Jewish New Year, is the only holiday I can think of where honey is an integral part of the celebration. Without honey, the New Year just isn't as sweet. I came across a really neat article published in the Toronto Star about the sweet new year connection - the article even tries to explain how honey can be kosher, even though it is made by bees. But the main part of the article is about Jewish beekeepers in the Toronto area who have a strong commitment to the environment and to connecting with the soil. It is an interesting story.

By the way, the gorgeous jar of honey in this photo is in season even after the holiday. You can check it out on the Oh! Nuts website.

Bees: Targeted and Poisoned!

Three million bees were apparently poisoned. The RCMP is investigating. A commercial beekeeper with about 1,200 colonies now has fewer than a thousand. The Winnipeg Free Press says that Manitoba beekeeper Jason Loewen suffered a "targeted attack." Beekeeper Loewen told the press, "If there was a disease, or if farmers had sprayed pesticide, those bees would've all been hit." Instead, apparently random colonies within four bee yards were attacked and residue was found on the boxes and lids. The hives are being tested to determine what sort of poison was used. Loewen lost 60 hives and another 40 were badly weakened.

|

Who kills bees? Other beekeepers, usually. Although, of course, I have no idea who would have wrecked Mr Loewen's bees, in other cases where honey beehives have been systematically ruined, the culprit often turned out to be other beekeepers. When I kept bees in Florida, it occasionally happened that big commercial outfits with dozens of outyards competed with other similar outfits for bee locations. Apiaries are often hard to get. If one fellow is doing just fine with his hives and someone else (usually from a northern state) suddenly appeared with a couple thousand hives, the first beekeeper would sometimes lose control of his rationality and damage the newcomer's property. A cheap way of hurting the other man's bees was to enter unguarded apiaries at night, dislodge lids, and dump gasoline from a jerry can into each cluster of bees. (I suppose you'd want to do this without lighting a smoker.) Cruel, mean, and effective. And one way to find oneself in the county jail. I was never targeted like that - I didn't have enough hives to make anyone nervous, but I knew people who were hit.

In the Manitoba case, reported to the police a couple of days ago, it is hard to imagine that the damage was done by a competing beekeeper. It is almost impossible to over-graze western Canada's flora and farmers usually are eager to have beekeepers on their land, so fights over forage and locations shouldn't exist. Besides, this is Canada. Such disputes are supposed to be settled over coffee at the village cafe. Not in the cover of darkness, jerry can in hand, eh?

Neonicotinoids and western Canada

|

I am still trying to understand why neonicotinoids have not been a problem in western Canada. 40% of all seeded crops in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta are canola. And 100% of the seed is treated with neonics. So, at least 40% of western Canada's cropland is treated with neonicotinoids every year. (I say "at least" because some of the other crops out here are also treated.) I just attended a meeting in which guest speaker Greg Sekulic, a canola growers' agronomist, spoke about the importance of bees to the canola growers. Greg spoke about the relationship of canola and bees, which can be boiled down to this: Canola needs bees; bees need canola. What's good for bees is good for canola. Simple enough. Canola seed is vastly more plentiful if healthy bee populations are around to pollinate it.